Boiling the Frog, One Tax at a Time

We all know the story about the frog and a pot of water. Toss the frog into boiling water and it will jump out immediately. Put the frog in cool water and slowly turn up the heat and it never notices the temperature rising until it’s too late. In today's progressively more socialist society (especially in blue states) we pass more "tax the rich" policies. The sad irony is that it's not the rich who end up paying more, it's our own children. Every single tax we have today started with the same slogan: "don't worry, this will only affect the top 1%".

We all know the story about the frog and a pot of water. Toss the frog into boiling water and it will jump out immediately. Put the frog in cool water and slowly turn up the heat and it never notices the temperature rising until it’s too late. In today's progressively more socialist society (especially in blue states) we pass more "tax the rich" policies. The sad irony is that it's not the rich who end up paying more, it's our own children. Every single tax we have today started with the same slogan: "don't worry, this will only affect the top 1%".

These taxes get approved by popular vote, and the threshold doesn't keep up with inflation. It's a familiar story. We see it play out over and over again:

- Federal telephone excise tax: This 3 % levy on local telephone service dates back to 1898. It was introduced to fund the Spanish‑American War at a time when telephones were rare and considered a luxury used only by the wealthy. Telephones became ubiquitous, yet the excise tax persisted for more than a century; it still applies to many landline bills today. What started as a “luxury tax” on rich early adopters turned into an automatic surcharge on an everyday utility.

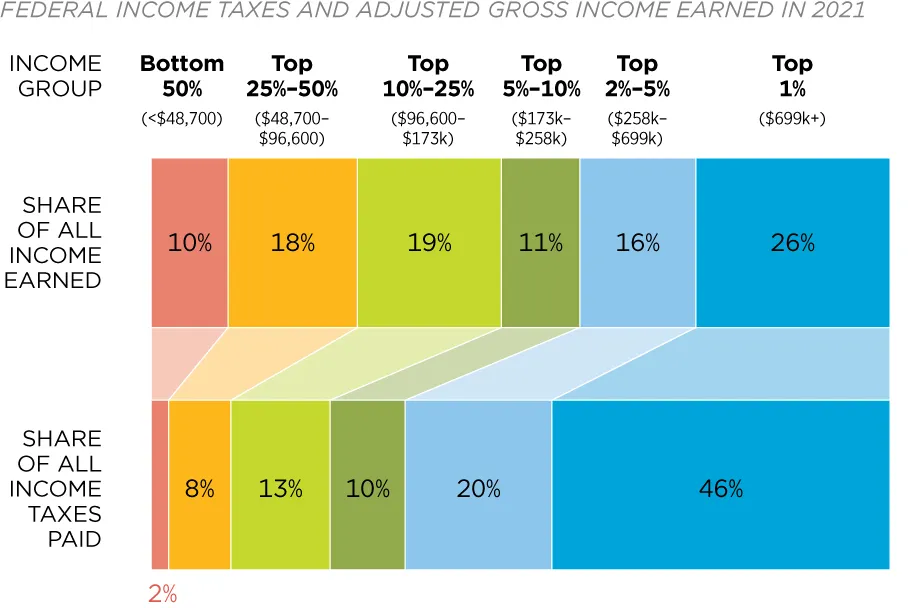

- Federal income tax: At its birth in 1913, the income tax hit a sliver of society. Generous exemptions and deductions meant that fewer than 1 % of Americans paid it, at a flat rate of 1 %. The tax code has been expanded and bracket thresholds haven’t always kept pace with nominal wage growth. Today the vast majority of workers file an income tax return each year and the top half of earners pay 98 % of all income tax revenue.

- Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT): Congress created the AMT in 1969 to force a few hundred wealthy households, who were using deductions to drive their tax bills to zero, to pay something. As Charles Schwab notes, the AMT was intended to crack down on high‑income taxpayers. Because its parameters weren’t indexed for inflation, rising incomes caused “normal households” to be swept into the AMT in subsequent decades. Only in 2017 did temporary reforms increase exemption thresholds and slow its reach, but absent further action those thresholds will lapse and bracket creep will resume.

“Tax the rich” used to mean less than 1 % of people

When the Sixteenth Amendment gave Congress the power to levy income taxes in 1913, the new tax was framed as a levy on the wealthy. There were generous exemptions and deductions. According to the National Archives, less than one percent of the population paid income taxes at a rate of 1 %. For most Americans the income tax didn’t exist.

Fast‑forward to today and the picture is very different. Federal income taxes are astonishingly progressive. The top 1 % of earners pay about 40 % of all federal income taxes. The top 10 % pay around 76 %. The top half of earners cover 98 % of the entire bill, while the bottom half pay just a couple percent. In the 1980s, the bottom half paid 7 % of taxes; by 2022 their share had shrunk to 2.96 %. Despite the rallying outcries that “the rich aren’t paying their fair share.”, the data show the opposite – the top earners already shoulder the vast majority of the burden.

Inflation quietly moves the goalposts

Why do regular workers end up paying taxes that were designed for the wealthy? Inflation and bracket creep. Bracket creep happens when nominal wages rise due to inflation but tax brackets fail to rise at the same rate. TurboTax explains that inflation can push taxpayers into higher brackets without increasing their real purchasing power; the IRS adjusts brackets using a chained consumer price index, but those adjustments often lag behind wage growth. Incidentally, taxation is one of the incentives for the government to under-represent inflation, something I already discussed in another blog post. The Manhattan Institute calls this unindexed system a hidden inflation tax that erodes the real value of deductions and pushes people into higher brackets, causing higher liabilities without any vote or debate. In New York, failure to index state taxes since 2016 has exposed workers to a compounding tax burden. Even low inflation compounds over time, slowly turning middle‑class families into “the rich” under static brackets.

It’s not just income taxes. Property assessments often rely on models that lag reality. Deloitte notes that high inflation can overstate the market value of income‑producing properties, and when assessments fall, tax rates typically rise to meet revenue requirements. Personal property acquired during inflation is valued at the inflated purchase price and that premium is captured every year for tax purposes. Local governments rarely lower mill rates when property values soar; instead they pocket the windfall and tell voters they’re keeping rates the same.

Why punishing “the rich” makes everyone poorer

There’s a deeper issue here than just bracket creep: who allocates capital better? When we vote to tax high earners more, we’re effectively transferring resources away from entrepreneurs, investors and small business owners – the people who build productive assets - and giving that money to politicians and bureaucrats. The assumption is that government will spend the money wisely for the common good. The evidence shows the opposite.

There’s a deeper issue here than just bracket creep: who allocates capital better? When we vote to tax high earners more, we’re effectively transferring resources away from entrepreneurs, investors and small business owners – the people who build productive assets - and giving that money to politicians and bureaucrats. The assumption is that government will spend the money wisely for the common good. The evidence shows the opposite.

The Cato Institute has chronicled a long history of government cost overruns. Projects estimated at $1 billion frequently double in cost. The Erie Canal, Panama Canal and other 19th‑century projects went 46 %, 142 % and 106 % over budget respectively. More recent examples are just as grim: Healthcare.gov’s costs jumped from $464 million to $824 million, the International Space Station quadrupled from $17 billion to $74 billion, and a VA hospital in Orlando more than doubled from $254 million to $616 million. Academic research cited by Cato finds around 90 % of large transportation projects go over budget, with rail projects averaging 45 % overruns and large dams averaging 96 %. These overruns aren’t accidents. Agencies face no penalty for underestimating costs; when projects run over, they simply request more funding. Private companies that mismanage costs go bankrupt; governments get bigger budgets.

When you tax private operators to fund public projects, you’re shifting assets from an environment where mismanagement is punished to one where mismanagement is rewarded. The result is less efficient investment, slower innovation and a smaller pie for everyone. That inefficiency shows up in long wait times at motor vehicle departments, crumbling infrastructure, schools that underperform despite ever‑higher budgets and a labyrinth of regulations that stifle new enterprise. Voters see the bad services and conclude we need even more taxes - a vicious cycle.

- Politicians promise to tax the rich to fund a new program.

- The top earners already pay the bulk of taxes, but the policy passes (majority vote).

- Inflation raises wages and property values, but tax thresholds don’t keep up.

- **More people move into higher brackets or face higher property taxes**.

- The money is allocated to projects with chronic cost overruns.

- Services don’t improve, voters demand new taxes to fix the problem.

The real problem isn't that we're not taxing the rich enough, but that our government failed to keep up with technology. It failed to keep up with good business practices. It failed to track its balance sheet, it failed to understand a simple formula that every real estate investor knows: revenue = profits - expenses. If expenses are growing faster than profits, we got a problem, regardless of how good the intentions were behind the misallocated expenses.