Rent Control: A Familiar Debate

It’s the summer of 2025, and Boston is once again flirting with a rent control policy. After nearly three decades without rent regulation, a new ballot question has ignited debate across the city. Proponents argue that capping rents will keep housing affordable for longtime residents. But beneath the surface of this well-intentioned idea lurks a history of domino-effect disasters. Boston’s own past - and dramatic episodes in other cities - reveal how an artificial cap on rents can trigger a cascade of unintended consequences.

It’s the summer of 2025, and Boston is once again flirting with a rent control policy. After nearly three decades without rent regulation, a new ballot question has ignited debate across the city. Proponents argue that capping rents will keep housing affordable for longtime residents. But beneath the surface of this well-intentioned idea lurks a history of domino-effect disasters. Boston’s own past - and dramatic episodes in other cities - reveal how an artificial cap on rents can trigger a cascade of unintended consequences.

Boston has been here before. From 1970 until the mid-1990s, rent control ordinances in places like Cambridge, Brookline, and Boston froze rents well below market levels. While this provided short-term relief for some tenants, it ultimately led to stagnation. Landlords had little incentive (or ability) to invest in upkeep when any improvements wouldn’t pay off due to capped rents. Over time, buildings deteriorated and new housing construction ground to a halt - a quiet warning of the deeper problems to come.

The Bronx Burns: A Domino Effect of Rent Control

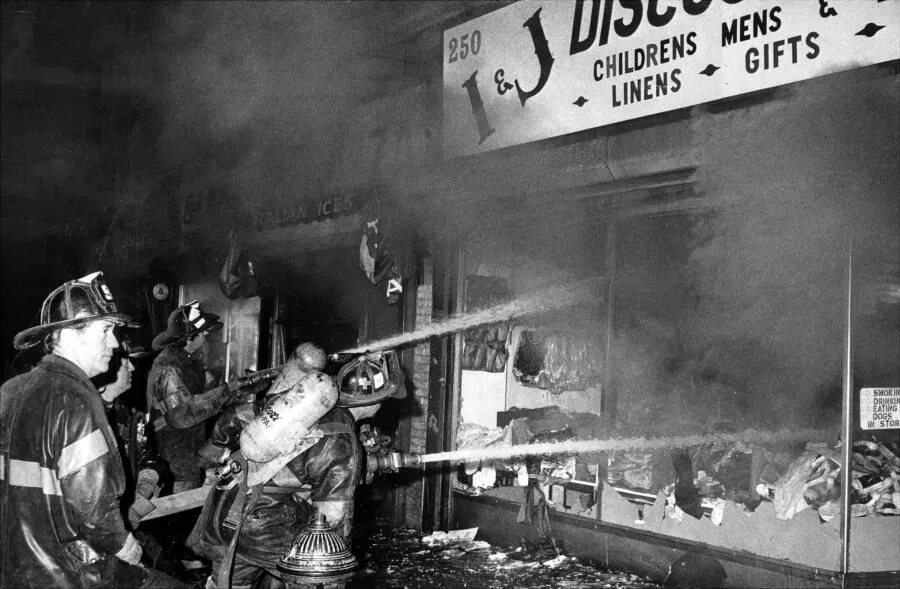

Firefighters battle a burning building in the South Bronx during the late 1970s.

Firefighters battle a burning building in the South Bronx during the late 1970s.

In New York City during the 1970s, rent control set the stage for one of the most harrowing urban collapses in American history. Entire blocks had been lost to landlord-set fires as rent control squeezed profits and made arson a tempting exit strategy. The Bronx, in particular, became the epicenter of a chain reaction driven by capped rents and rising costs. It started as a well-meaning effort to keep housing affordable - but ended with neighborhoods in flames. Here’s how one domino toppled the next:

- Artificial Rent Cap – The First Domino: City policies froze rents below market rates. Tenants initially rejoiced at the affordable prices, but this artificial price constraint meant landlords could no longer adjust rents to keep up with inflation or rising expenses. In the 1970s, inflation soared into double digits, yet rent-controlled apartments were stuck with only minimal (or no) allowable increases. This put many owners in a financial bind.

- Rising Costs, Shrinking Margins: As the years went on, the cost of everything – heating fuel, property taxes, maintenance materials - kept climbing, while landlords’ rental income stayed flat. A rent-controlled building that might have been modestly profitable in 1970 turned into a money-loser by 1975. Landlords found themselves squeezed by fixed rents and growing bills, with no ability to raise revenue to cover the gap. The real (inflation-adjusted) rent they received fell each year, eroding any profit margin.

- Maintenance Falls Apart: Facing a budget crunch, many landlords cut back on building upkeep. Repairs were deferred or ignored. Spending $10,000 on a new roof made little sense if you couldn’t raise the rent to pay for it. Over time, paint peeled, roofs leaked, and heating systems broke down. Housing quality began to decay.

- Supply Shrinks – New Construction Stalls: Another consequence of the price cap soon emerged: developers and owners lost any incentive to build new rental housing or even to continue offering existing units for rent. With profits capped, investors fled the housing market. Some landlords kept units vacant or converted apartments to other uses to avoid rent regulation. The overall supply of available housing constricted, making apartments harder to find. At the very moment rent control was supposed to help renters, it created a housing shortage.

- Abandonment and Arson – The Final Domino: As conditions worsened, a grim endgame unfolded. Some landlords simply walked away from their properties, leaving buildings empty rather than continue bleeding money. Others chose an even darker path: they realized the insurance value of their buildings was higher than the sale value or the income from rent. In other words, a building was worth more burned down than alive. A wave of arson-for-profit swept the Bronx. Desperate or unscrupulous owners hired torches to set their own buildings ablaze so they could collect insurance payouts instead of persisting with unprofitable rentalsBlock by block, nighttime fires became routine.. During the late ’70s the South Bronx earned the infamous nickname “the Bronx is burning.” Firefighters raced from one inferno to the next, but it was a losing battle. By the end of the 1970s, nearly 80% of the housing stock in the South Bronx was lost to fire, and roughly 250,000 residents were displaced from their homes. Entire neighborhoods turned into smoldering ruins. The final domino had fallen - a policy meant to protect renters ended up destroying their communities.

The Bronx’s collapse was a dramatic lesson in how a well-intentioned policy can backfire catastrophically. Each step in the chain made logical sense once rent control set the process in motion: frozen rents led to landlord losses; losses led to disinvestment and decay; decay led to abandonment and arson. In the aftermath, even politicians and residents who had supported rent control could not ignore the results. New York City had to pour resources into emergency housing and eventually began slowly loosening some regulations to stabilize the situation. The Bronx would struggle for years to recover from the problems triggered by artificial rent limits. And notably, public housing projects in the Bronx - which were not subject to the same profit motives - did not burn, highlighting how it was the distorted incentives of rent-controlled private housing that fueled the fire crisis.

Lessons from Boston’s Past and Beyond

Boston never saw a catastrophe on the scale of the Bronx fires, but witnessed the same economic forces at work on a smaller scale. From 1970 until rent control ended in 1994, Boston and its neighboring cities of Cambridge and Brookline had strict rent control policies. Rents in controlled units were kept far below market rates (often 40%+ lower than similar non-regulated apartments nearby). At first this kept housing cheap for select tenants. However, over the years, local landlords faced the same squeeze between rising costs and fixed income. Many properties in Cambridge and Boston fell into disrepair.

Boston never saw a catastrophe on the scale of the Bronx fires, but witnessed the same economic forces at work on a smaller scale. From 1970 until rent control ended in 1994, Boston and its neighboring cities of Cambridge and Brookline had strict rent control policies. Rents in controlled units were kept far below market rates (often 40%+ lower than similar non-regulated apartments nearby). At first this kept housing cheap for select tenants. However, over the years, local landlords faced the same squeeze between rising costs and fixed income. Many properties in Cambridge and Boston fell into disrepair.

When Massachusetts voters narrowly approved a referendum to eliminate rent control in 1994, the effects were dramatic. Landlords who could finally charge sustainable rents, unlocking a wave of reinvestment. Over the next decade, formerly rent-controlled buildings in Cambridge saw their market values jump by roughly 45% as owners repaired, upgraded, and modernized them. Lifting the rent cap removed a weight that had been dragging neighborhoods down. What seemed like a renter-friendly policy had been quietly undermining the very fabric of those communities.

Boston’s past mirrored the Bronx in one key respect: rent control shrank the housing supply. In New York, it happened via abandonment and arson; in Boston, it happened more subtly. Through the 1980s, virtually no new rental housing was built in Cambridge or Boston’s controlled neighborhoods - developers built elsewhere or not at all. Some landlords converted apartments to condominiums or chose to leave units vacant rather than subject them to strict regulation. The outcome was the same: fewer homes available in the long run. Supply-demand curves don't care about politics, and the ripple effects of messing with them are far-reaching.

A recent Stanford study of San Francisco’s rent control expansion in the 1990s found the same result: rent control caused a 15% decline in the number of rental units as landlords pulled units off the market or redeveloped buildings, leading to higher rents in the long term due to the reduced supply. In San Francisco’s case, the researchers concluded that rent control ultimately fueled gentrification - the policy intended to help low-income residents ended up encouraging landlords to replace affordable units with upscale condos and attracted even wealthier tenants, exacerbating inequality. The city “protected” some incumbent renters at the expense of a broader housing crisis for the next generation.

From Stockholm’s notorious decades-long apartment waitlists to Berlin’s recent failed experiment with rental price caps, the story repeats: whenever rents are held artificially low by law, the housing supply withers and the people it’s meant to help often end up worse off. Everyone ends up worse off. Builders stop building. Owners neglect their properties or find ways to escape the system. Neighborhoods decay. Sometimes the decay is slow and hidden; other times - as in 1970s New York - it’s sudden and tragic.

The Fundamental Flaw

Rent control treats the symptoms (high prices), not the cause (high operating cost). A price cap doesn’t make costs disappear. Landlord’s expenses for taxes, heat, repairs, and mortgages are rising year after year. Even with a baked-in factor of "maximum allowed annual increase", this flawed design assumes that landlords raise rents consistently and that other market forces are subject to the same cap. For rent control to make sense, we need a bunch of other "controls" to go along with it:

- Tax control

- Utility cost control

- Wage control

- Material cost control

At this point we're no longer talking about rent, we're taking a snapshot in time and forcing it on the society as a whole - "Soviet Union"-style. The real problem isn't rents, but the high cost of living in Boston because the very politicians arguing for rent control never ran a business in their life and can't budget their books. For rents to be more reasonable in Boston, the cost of doing business needs to be more reasonable in Boston.