Market Cycles Case Study: Chicago

Chicago's Claim to Fame

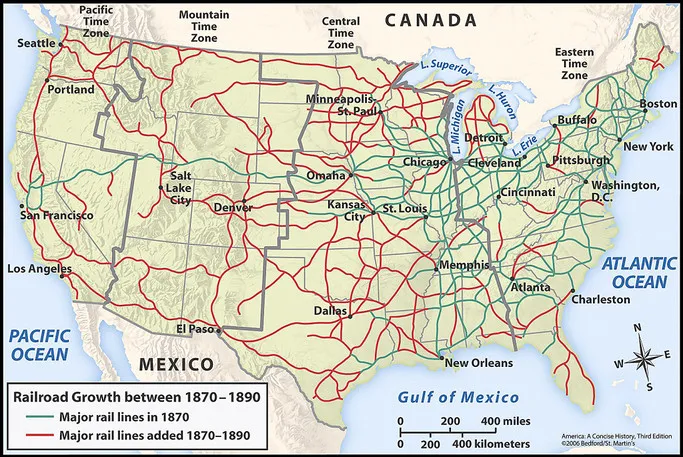

Before Chicago became a global city, it was first a logistics solution. Chicago’s rise was not driven by a single industry, but by its position at the intersection of America’s economic geography. Sitting between the agricultural heartland of the Midwest and the industrial centers of the East, Chicago became the natural transfer point for goods, capital, and labor. Railroads converged there, waterways connected it to the Great Lakes and the Mississippi system, and markets followed infrastructure. By the mid-19th century, Chicago was already indispensable - not because of what it produced, but because of how efficiently it moved everything else. Grain, lumber, meat, and manufactured goods all passed through Chicago, making it the nervous system of a rapidly industrializing nation.

That logistical advantage compounded quickly. As rail networks expanded, Chicago became the headquarters city for entire industries rather than a factory town tied to a single product. Stockyards, commodities exchanges, banks, insurance firms, and manufacturers clustered together, feeding off one another. The city grew dense, diverse, and economically layered. Unlike Detroit’s later hyper-specialization, Chicago’s growth was structurally diversified from early on. Capital flowed in not just to build things, but to organize markets. By 1870, Chicago was already one of the fastest-growing cities in the world, attracting entrepreneurs, immigrants, and institutions at scale.

That logistical advantage compounded quickly. As rail networks expanded, Chicago became the headquarters city for entire industries rather than a factory town tied to a single product. Stockyards, commodities exchanges, banks, insurance firms, and manufacturers clustered together, feeding off one another. The city grew dense, diverse, and economically layered. Unlike Detroit’s later hyper-specialization, Chicago’s growth was structurally diversified from early on. Capital flowed in not just to build things, but to organize markets. By 1870, Chicago was already one of the fastest-growing cities in the world, attracting entrepreneurs, immigrants, and institutions at scale.

Then came what should have been an existential blow: the Great Chicago Fire. In 1871, much of the city burned to the ground. In the short term, it was catastrophic - thousands of buildings destroyed, businesses displaced, and residents uprooted. But instead of triggering a doom loop, the fire produced something rare: a positive feedback loop of confidence and reinvestment. Chicago rebuilt rapidly, using fire-resistant materials, modern planning, and ambitious architecture. The reconstruction became a national story. Capital flooded in, talent followed, and the city rebranded itself not as fragile, but as resilient, modern, and forward-looking. What looked like a disaster became a proof point: Chicago could absorb shocks and come back stronger.

The fire allowed Chicago to reset its physical infrastructure while preserving its economic role. It used catastrophe as a narrative and structural reboot. That early episode set a pattern that would define Chicago’s long-term trajectory: shocks would come, but the city’s underlying function - as a connector of markets, labor, and capital - remained intact.

Chicago’s Golden Age: Scale, Diversification, and Institutional Power

Chicago’s golden age was not defined by a single peak year, but by a long stretch - roughly from the late 19th century through the mid-20th century - during which the city became one of the most powerful economic nodes in the world. What distinguished Chicago at its height was not just growth, but the breadth of its economic base. While many industrial cities were tied to one dominant output, Chicago sat at the crossroads of multiple systems: transportation, finance, commodities, manufacturing, retail, and labor. This diversification made growth self-reinforcing. When one sector slowed, others absorbed capital and workers, stabilizing the overall system.

Chicago’s golden age was not defined by a single peak year, but by a long stretch - roughly from the late 19th century through the mid-20th century - during which the city became one of the most powerful economic nodes in the world. What distinguished Chicago at its height was not just growth, but the breadth of its economic base. While many industrial cities were tied to one dominant output, Chicago sat at the crossroads of multiple systems: transportation, finance, commodities, manufacturing, retail, and labor. This diversification made growth self-reinforcing. When one sector slowed, others absorbed capital and workers, stabilizing the overall system.

At the center of this era was Chicago’s role as a market-maker. Institutions like the Chicago Board of Trade and later the Chicago Mercantile Exchange didn’t merely facilitate trade; they standardized it. Futures contracts, price discovery, and risk hedging transformed how agriculture and commodities functioned nationally. Farmers in Iowa, ranchers in Texas, and manufacturers in the Northeast all depended on Chicago’s exchanges to operate efficiently. This positioned the city not just as a participant in the economy, but as an organizer.

Physically and culturally, the city reflected this confidence. Chicago became a proving ground for modern architecture and urban design. The skyline that emerged in the early 20th century was not ornamental; it was functional, dense, and unapologetically commercial. Headquarters clustered downtown, rail yards and ports moved goods at scale, and neighborhoods formed around employment rather than speculation. The city invested heavily in infrastructure (transit, water, and sanitation). This created a virtuous cycle: efficient infrastructure attracted businesses, businesses attracted labor, and labor supported institutions that further reinforced growth.

By the mid-20th century, Chicago had become a true command city - not just large, but indispensable. Corporate headquarters, banks, law firms, universities, and cultural institutions coexisted in a dense ecosystem that made the city difficult to bypass. Importantly, Chicago’s success did not depend on permanent national dominance or government protection. It depended on relevance. As long as goods needed to move, prices needed to be discovered, and capital needed to be coordinated, Chicago had a role to play. That structural relevance is what made its golden age durable, and why its later challenges would look fundamentally different from cities whose fortunes were tied to a single industry or moment in time.

Chicago’s Long Slowdown: From Dominance to Drag

Chicago did not collapse the way Detroit did. It stalled. Its decline played out as a series of friction increases rather than a single failure mode. Each stage introduced constraints that reduced growth, raised costs, added layers of bureaucracy - Individually survivable, collectively limiting.

Stage 1: Deindustrialization Without Disappearance (1950s–1970s)

Like every major American city, Chicago was hit by postwar deindustrialization. Manufacturing employment declined, rail yards shrank, and the stockyards that once symbolized Chicago’s industrial muscle were dismantled. But unlike Detroit, this did not immediately hollow out the city. Chicago’s advantage was that industrial decline did not equal economic obsolescence. Finance, commodities trading, logistics, and corporate services absorbed some of the shock.

The problem was more subtle. The jobs that disappeared were often middle-income, unionized, and geographically dispersed across the city. The jobs that replaced them were more centralized, more credentialed, and fewer in number. This introduced a mismatch between the city’s physical footprint, workforce composition, and emerging economic base. Chicago didn’t lose relevance, but it lost velocity.

Stage 2: Governance Friction and the Cost of Being Big (1970s–1990s)

As Chicago matured, the same institutions that once stabilized it began to introduce drag: a large public sector, entrenched political structures, and complex labor agreements. Maintaining legacy infrastructure, pension systems, and public payrolls became increasingly expensive as population growth flattened.

Unlike cities that shrank dramatically, Chicago retained scale. That meant it never hit a crisis point that forced a hard reset. Instead, it drifted into managed stagnation: budgets balanced through incremental tax increases, borrowing, and deferred maintenance. From the outside, the city still functioned. From the inside, costs quietly compounded.

This era also saw rising divergence between the urban core and many outlying neighborhoods. Downtown and select North Side areas remained economically vibrant, while large portions of the South and West Sides experienced persistent disinvestment.

Stage 3: Globalization and the Hollowing Middle (1990s–2008)

By the 1990s and early 2000s, Chicago had successfully repositioned itself as a global city. Finance, consulting, legal services, and corporate headquarters flourished. But this success masked a growing structural weakness: growth became increasingly concentrated at the top. High-skill, high-income jobs expanded, while middle-tier employment lagged.

Globalization amplified this effect. Capital and talent became more mobile. Chicago could still attract both, but now it was competing not just with New York or Los Angeles, but with lower-cost cities domestically and internationally - many with much better climate (as anyone familiar with Chicago winters can attest). The city remained attractive, but no longer uniquely so. Each marginal decision (where to open an office, where to expand, where to hire) became more sensitive to taxes, regulation, and cost of living.

Stage 4: The Illusion of Stability Pre-2008

By the mid-2000s, Chicago appeared stable. Downtown development was strong. Tourism was healthy. Corporate presence remained significant. But underneath that stability was a balance sheet under strain. Pension obligations had grown, infrastructure was aging, and population growth had stalled. The city was no longer expanding its tax base fast enough to offset long-term liabilities.

A Different Kind of Decline

Chicago’s story from its golden age to 2008 is not one of failure, but of accumulated constraint. The city survived forces that destroyed others precisely because it was complex, diversified, and institutionally strong. But those same traits also allowed problems to be postponed rather than resolved.

Chicago recovery from the 2008 crash (2012+)

Chicago took significantly longer to recover from 2008 crash than other cities, especially the South Side. It was not uncommon to find $60k brick bungalows on MLS as late at 2016 - ones that sell over $200k today. Chicago did not reach its pre-2008 peak until 2012.

- Chicago peak: Apr 2007 ≈ $252.9k

- Chicago trough: Dec 2012 ≈ $164.5k (-35.0%)

- Back to prior peak: Feb 2021

By comparison, the U.S. series hit its pre-crash peak again around Jan 2017.

Modern-Day Chicago

Using Zillow’s ZHVI (typical “middle-tier” home value; smoothed, seasonally adjusted) series, latest point is Nov 2025.

Using Zillow’s ZHVI (typical “middle-tier” home value; smoothed, seasonally adjusted) series, latest point is Nov 2025.

Typical home value (ZHVI)

| Jan 2010 | Feb 2020 (pre-COVID) | Jun 2022 | Nov 2025 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicago MSA | $198,657 | $238,010 | $295,704 | $334,512 |

| United States | $171,158 | $247,825 | $342,935 | $359,241 |

Pre-COVID and Post-COVID Growth

- 2010 → Nov 2025: Chicago +68.4% vs U.S. +109.9%

- Pre-COVID (Feb 2020) → Jun 2022: Chicago +24.2% vs U.S. +38.4%

- Jun 2022 → Nov 2025: Chicago +13.1% vs U.S. +4.8%

- Pre-COVID → Nov 2025: Chicago +40.5% vs U.S. +45.0%

Note: metrics were updated after the initial publication of the blog

North, South, and West Chicago

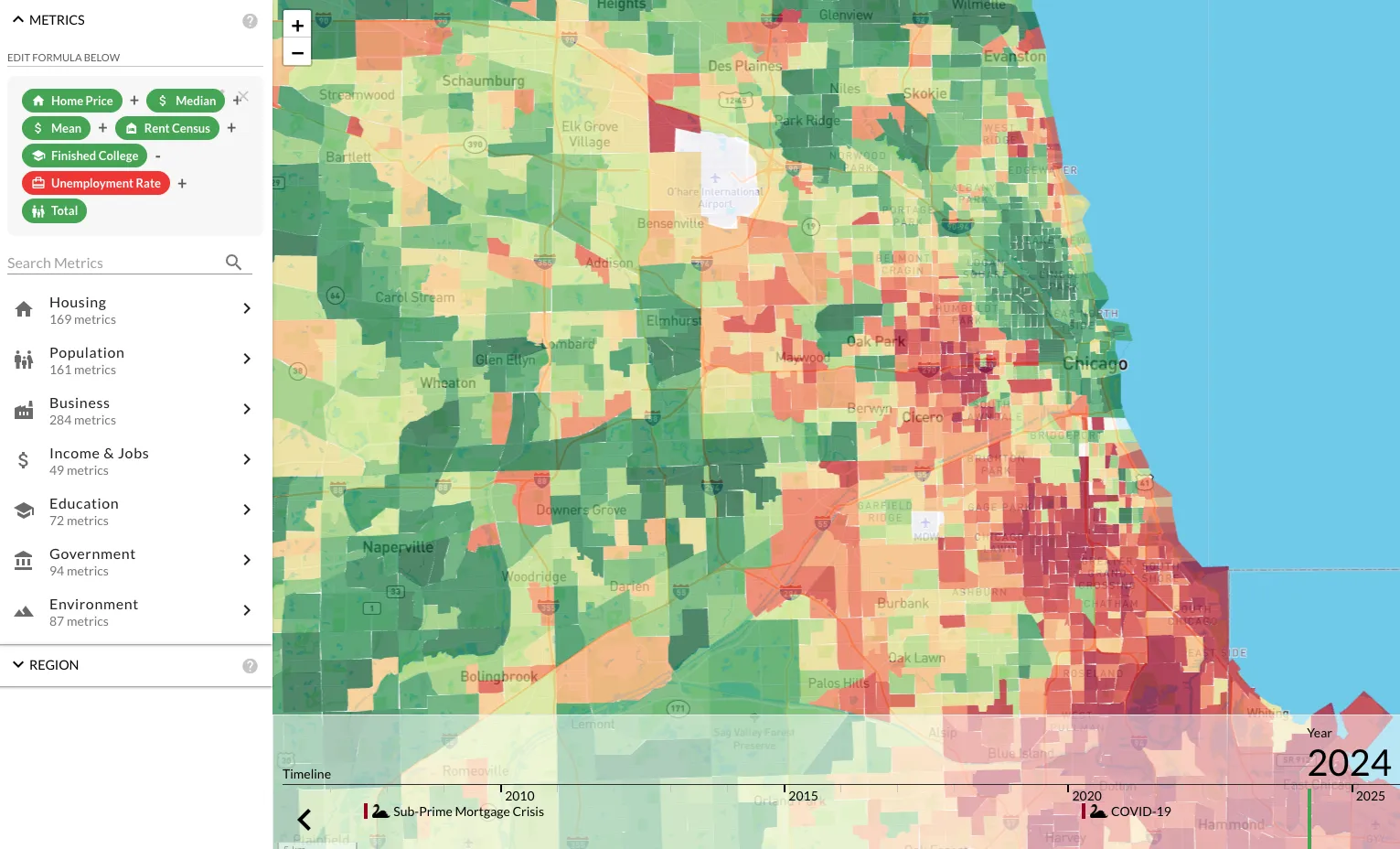

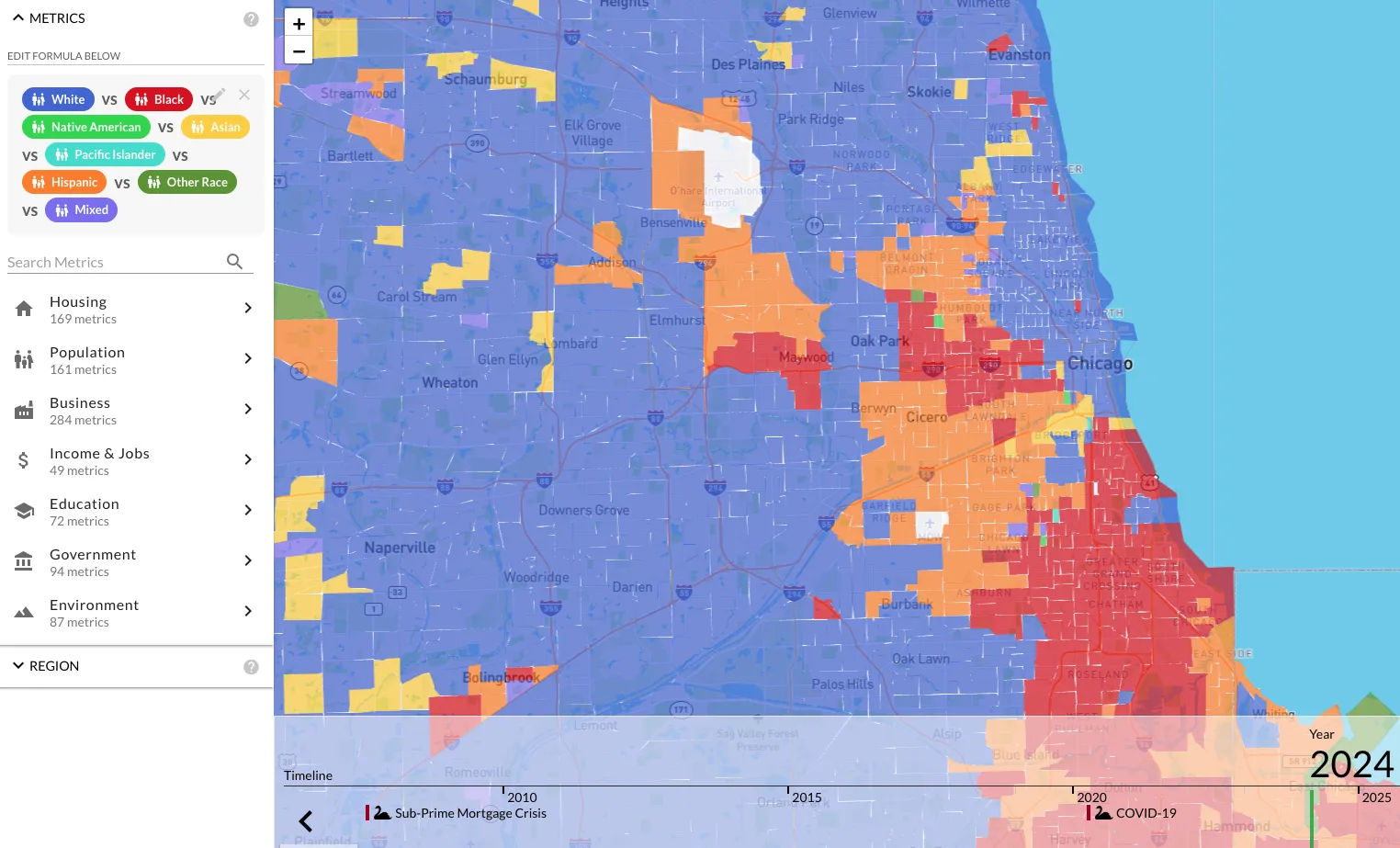

Chicago is heavily segregated and there is huge income disparity between North and South side of Chicago:

Chicago is heavily segregated and there is huge income disparity between North and South side of Chicago:

- North Side: median sale price ~$662K (very competitive)

- South/West Side: median sale price ~$266K (much softer)

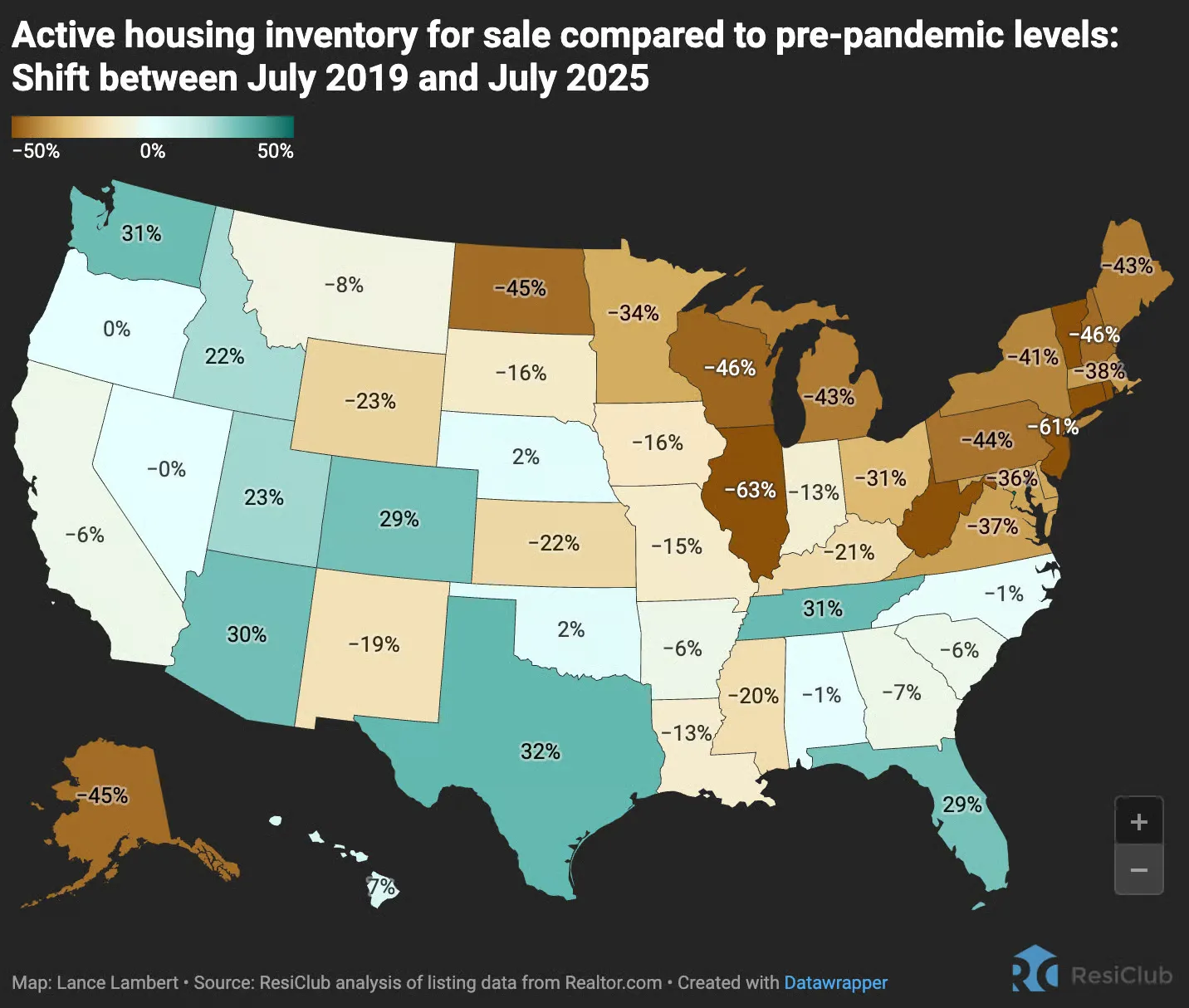

Chicago is not going anywhere as a city, but the same can't be said about certain suburbs. Throughout 2010-2020, Chicago ran a large program to demolish abandoned properties. This program probably contributed to the post-COVID scarcity Chicago is experiencing now:

Source: ResiClub

Source: ResiClub