Market Cycles Case Study: Detroit

The Golden Age of Detroit

Before Detroit became shorthand for urban decline, it was one of the most successful cities in the world. Detroit emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a direct response to powerful market forces: industrialization, transportation economics, and the explosive demand for mechanized mobility. Detroit’s geography mattered. Sitting on the Great Lakes and connected to rail networks, it was ideally positioned for moving raw materials like iron ore, coal, and timber, and for shipping finished goods to a rapidly growing national market. Long before cars, Detroit was already an industrial and logistics hub.

Before Detroit became shorthand for urban decline, it was one of the most successful cities in the world. Detroit emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a direct response to powerful market forces: industrialization, transportation economics, and the explosive demand for mechanized mobility. Detroit’s geography mattered. Sitting on the Great Lakes and connected to rail networks, it was ideally positioned for moving raw materials like iron ore, coal, and timber, and for shipping finished goods to a rapidly growing national market. Long before cars, Detroit was already an industrial and logistics hub.

The real inflection point came with the automobile. As cars shifted from luxury novelties to mass-market necessities, Detroit became the center of gravity for an entirely new industry. The city attracted capital, labor, and talent at a scale few places could match. Vertical integration dominated the era: factories clustered tightly, suppliers located nearby, and skilled workers followed the jobs. Wages were high by contemporary standards, especially in manufacturing, which drew millions of migrants from rural America and immigrants from Europe. Between 1900 and 1950, Detroit’s population exploded, and with it came dense neighborhoods, robust tax revenues, and an expanding middle class.

By 1950, Detroit represented the peak expression of industrial capitalism done at scale. The city was wealthy, confident, and highly specialized. Its success rested on a simple but powerful formula: a dominant industry with global demand, a workforce paid well enough to consume what it produced, and infrastructure built to support both. Importantly, the conditions that made Detroit thrive were specific to that moment in history. They were the product of technology, transportation costs, labor dynamics, and geopolitical realities that favored centralized manufacturing.

The Doom Loop: How Detroit Unwound After Its Peak

Detroit hit its peak population in 1950 (the Census lists Detroit city at 1,849,568), after that the trend was mostly downhill. But the job exodus began even before that. Historian Thomas Sugrue describes the auto industry restructuring and decentralizing in the postwar era, noting that between 1948 and 1967 Detroit lost more than 130,000 manufacturing jobs, even while the auto industry was near its overall peak. Detroit still looked like a booming industrial giant for years, even while already losing jobs.

Detroit’s decline was not sudden, and it was not caused by a single decision or villain. It was a self-reinforcing economic feedback loop, triggered by structural shifts in industry and then amplified by policy responses that unintentionally accelerated capital and population flight. Once the loop started, each attempt to stabilize the city’s finances made the next stage worse.

Loss of Businesses and Jobs

The first break in the system was the loss of businesses, particularly in manufacturing. After 1950, the U.S. auto industry began decentralizing production. Advances in logistics, highways, and automation reduced the need for tightly clustered factories. Automakers moved plants to lower-cost regions, including the suburbs, the American South, and eventually overseas. This wasn’t unique to Detroit, but Detroit was uniquely exposed because of how concentrated its economy was. By mid-century, the city’s tax base was overwhelmingly tied to a single industry. When auto employment began to decline, there was no equally large replacement sector to absorb displaced workers. Between 1950 and 1970, Detroit lost hundreds of thousands of manufacturing jobs, even as the national economy grew.

Shrinking Revenue / Tax Base

As businesses left, the city’s revenue base shrank, but its obligations did not. Infrastructure, public services, and pensions had been built for a city of nearly two million people. Instead of shrinking expenditures to match a smaller economy, the city attempted to maintain service levels by raising taxes. Detroit steadily increased property tax rates, income taxes, and business taxes throughout the second half of the 20th century. According to data from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and Michigan state records, Detroit eventually had one of the highest effective property tax burdens in the country. This mattered because capital is mobile. As taxes rose inside city limits, businesses and higher-income residents increasingly chose to relocate.

Better Alternatives

This is where suburban policy divergence became decisive. Suburbs surrounding Detroit offered newer housing, lower taxes, newer schools, and fewer legacy costs. Importantly, they also benefited from federal policies that unintentionally favored decentralization, including highway construction and mortgage subsidies that made suburban homeownership cheaper and more accessible. As middle-class and upper-income households moved out, Detroit lost not just population, but disproportionately high earners. Census data shows that while Detroit’s population fell by roughly 60 percent from its 1950 peak to 2010, its tax base declined even faster because the people leaving were those most capable of paying.

Rising Taxes

The city responded to this erosion by raising taxes further, which accelerated the out-migration. This is the core of the doom loop: fewer businesses → less revenue → higher taxes → more departures → even less revenue.

By the 1970s and 1980s, Detroit was caught in a fiscal vise. Each remaining resident and business had to shoulder a larger share of the city’s fixed costs. For many, it simply became irrational to stay. This pattern is well documented in urban economics literature and is often cited as a textbook case of tax-base erosion.

Abandoned Properties

As population density collapsed, abandoned property became unavoidable. Entire neighborhoods lost critical mass. When homes are vacant, property values fall; when property values fall, tax revenue falls; when tax revenue falls, city services degrade. Detroit was left maintaining roads, utilities, and public safety across a physical footprint designed for a much larger city, but with a fraction of the resources. Vacant structures also created negative externalities: fires, vandalism, and blight spread rapidly. According to city and FBI Uniform Crime Reports, crime rose sharply in periods following major population losses, not because of some inherent urban pathology, but because economic opportunity and social cohesion collapsed simultaneously.

Rising Crime

Crime further reinforced the loop. Rising crime increased insurance costs, discouraged investment, and pushed out remaining residents who could afford to leave. Businesses faced higher security costs and lower foot traffic. Property owners abandoned buildings that were worth less than their tax and maintenance liabilities. By the time Detroit declared bankruptcy in 2013, the city had tens of thousands of vacant structures and a tax base that could no longer support even basic operations. The bankruptcy itself did not cause the decline; it merely formalized a collapse that had been unfolding for decades.

The Aftermath

Detroit failed because it was over-specialized, slow to adapt, and trapped in a fiscal structure that punished those who stayed. Once the doom loop took hold, rational individual decisions (leaving for better opportunities, lower taxes, and safer neighborhoods) collectively produced an irrational outcome for the city as a whole. Detroit wasn’t destroyed by a single shock. It was undone by a compounding sequence of incentives that, once set in motion, became extraordinarily difficult to reverse.

Detroit failed because it was over-specialized, slow to adapt, and trapped in a fiscal structure that punished those who stayed. Once the doom loop took hold, rational individual decisions (leaving for better opportunities, lower taxes, and safer neighborhoods) collectively produced an irrational outcome for the city as a whole. Detroit wasn’t destroyed by a single shock. It was undone by a compounding sequence of incentives that, once set in motion, became extraordinarily difficult to reverse.

When budgets are under pressure, tax hikes allow politicians to claim fiscal responsibility without cutting services, renegotiating obligations, or confronting structural inefficiencies. On paper, the math works. Raise rates, close the gap, move on. The problem is that cities are not static balance sheets. They are competitive systems. Every tax increase changes behavior at the margin, and those margins compound over time.

Detroit’s leadership repeatedly chose higher taxes as a stopgap. Each increase was justified as necessary, temporary, or modest. But taken together, they sent a clear signal to residents and businesses who had options: staying meant paying more for declining services, while leaving meant immediate financial relief. The people most capable of absorbing higher taxes (homeowners with equity, profitable businesses, skilled workers) were also the people most able to relocate. Over time, this inverted the tax base. Those least able to leave were left carrying an ever-growing share of the burden, while the city hollowed out around them. What looked like a solution became an accelerant.

This dynamic is not unique to Detroit, and it is not confined to history. Michelle Wu’s 2024 proposal to shift Boston’s tax burden more heavily onto residential property owners. The policy was framed as a fairness adjustment and a way to stabilize city finances without cutting services. In isolation, the increase appeared manageable. But the underlying logic mirrors the early stages of Detroit’s loop: when faced with fiscal pressure, lean on immobile taxpayers rather than addressing cost structures or long-term competitiveness. In a city like Boston, where residents are already highly mobile and remote work has expanded exit options, even small policy shifts can influence long-term location decisions.

The risk is not that one tax increase causes collapse. The risk is that repeated reliance on taxation as a primary tool substitutes political convenience for economic strategy. Cities begin to assume that demand is permanent, that residents will tolerate incremental increases indefinitely, and that exits will be marginal. Detroit made that assumption for decades. It was wrong. Once confidence erodes and alternatives become attractive, behavior changes quickly, and reversing course becomes exponentially harder.

The lesson from Detroit is that tax policy cannot be treated as a neutral lever. It shapes migration, investment, and risk-taking. When taxes rise in response to decline rather than growth, they tend to reinforce the very forces they are meant to counteract. By the time the feedback loop becomes visible in crime, abandonment, and insolvency, the underlying incentives have already done their work.

Detroit’s aftermath is a warning about how fragile complex systems become when short-term fixes replace long-term thinking. Cities rise when they align incentives with productivity and adaptation. They fall when they try to tax their way out of structural problems. The difference between the two paths is often invisible at first, until it isn’t.

Today

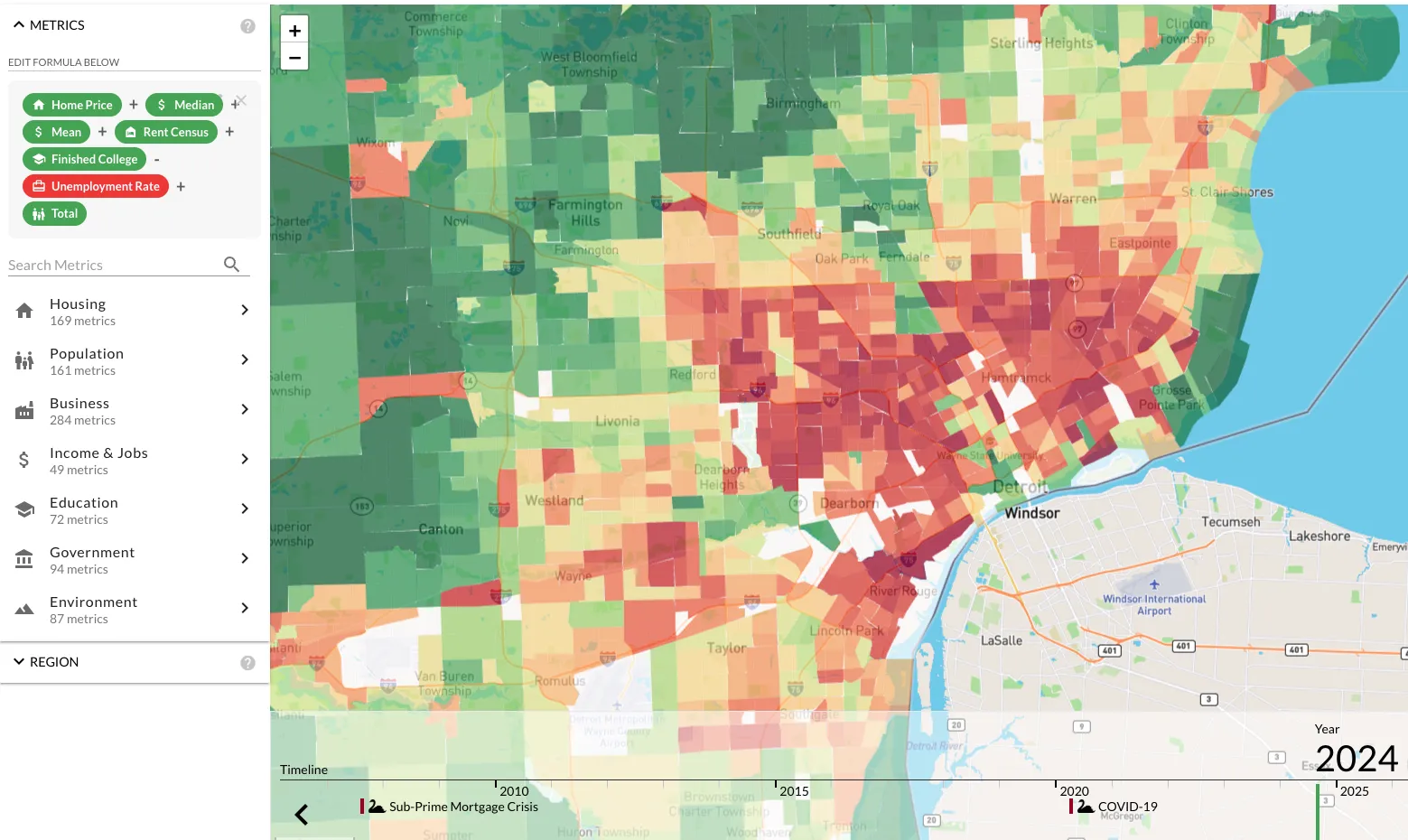

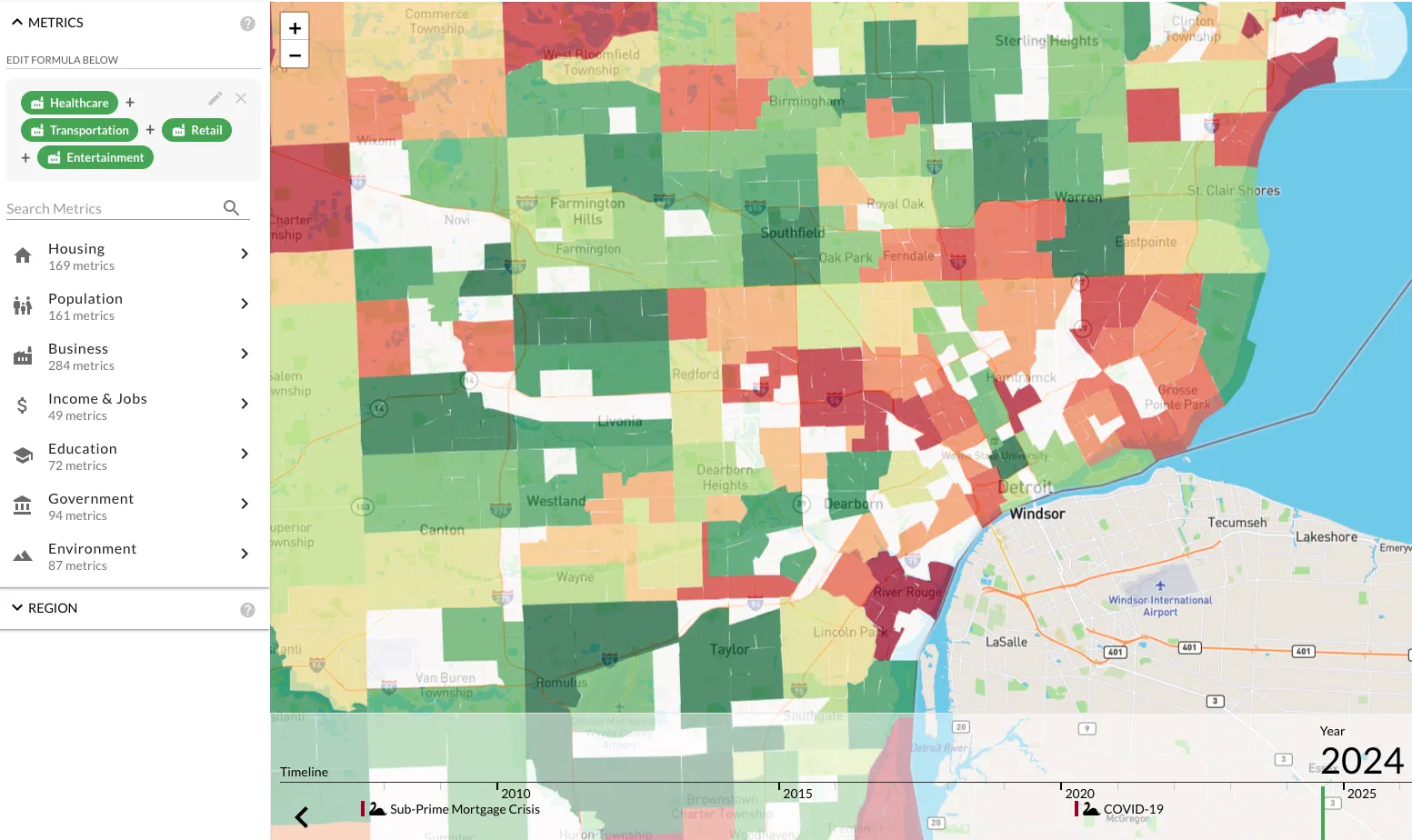

Post-COVID Detroit is a low-cost city with high variance: pockets of real momentum (healthcare, logistics, downtown/Midtown services, small manufacturing, trades, and the auto supply chain reinventing itself) sitting next to neighborhoods where demand is still fragile and the “cheap” price tag is a trap once you price in rehab, taxes, insurance, vacancies, and management.

Post-COVID Detroit is a low-cost city with high variance: pockets of real momentum (healthcare, logistics, downtown/Midtown services, small manufacturing, trades, and the auto supply chain reinventing itself) sitting next to neighborhoods where demand is still fragile and the “cheap” price tag is a trap once you price in rehab, taxes, insurance, vacancies, and management.

Post-COVID growth estimates (data originally from Zillow):

- Detroit metro typical value: ~$177k (Feb 2020) → ~$231k (Jun 2022) = +30%; and → ~$256k (Nov 2025) = +44% since pre-COVID.

- U.S. typical value: ~$248k (Feb 2020) → ~$343k (Jun 2022) = +38%; and → ~$359k (Nov 2025) = +45% since pre-COVID.

Rents (Detroit metro vs U.S.):

- Detroit metro rent index: ~$1,050 (Feb 2020) → ~$1,331 (Jun 2022) = +27%; and → ~$1,481 (Nov 2025) = +41% since pre-COVID.

- U.S. rent index: ~$1,424 (Feb 2020) → ~$1,760 (Jun 2022) = +24%; and → ~$1,925 (Nov 2025) = +35% since pre-COVID.

Detroit grew dramatically in nominal terms, but mostly due to inflationary pressure, home prices kept pace with the rest of the US (but mostly because they started much cheaper) and rents outpaced the US average. Today, It's a good cashflow market, but the city population as a whole is shrinking (which also means fewer city services) and you have to price that risk in. Detroit is probably NOT for remote investing, and any growth over the next decade will likely be powered by inflationary pressure rather than true income-producing activity. Even so, any investment appreciates compared to cash - including Detroit real estate. Anyone who sat on the sidelines ultimately lost money in terms of purchasing power.