Affordable Housing is a Scam

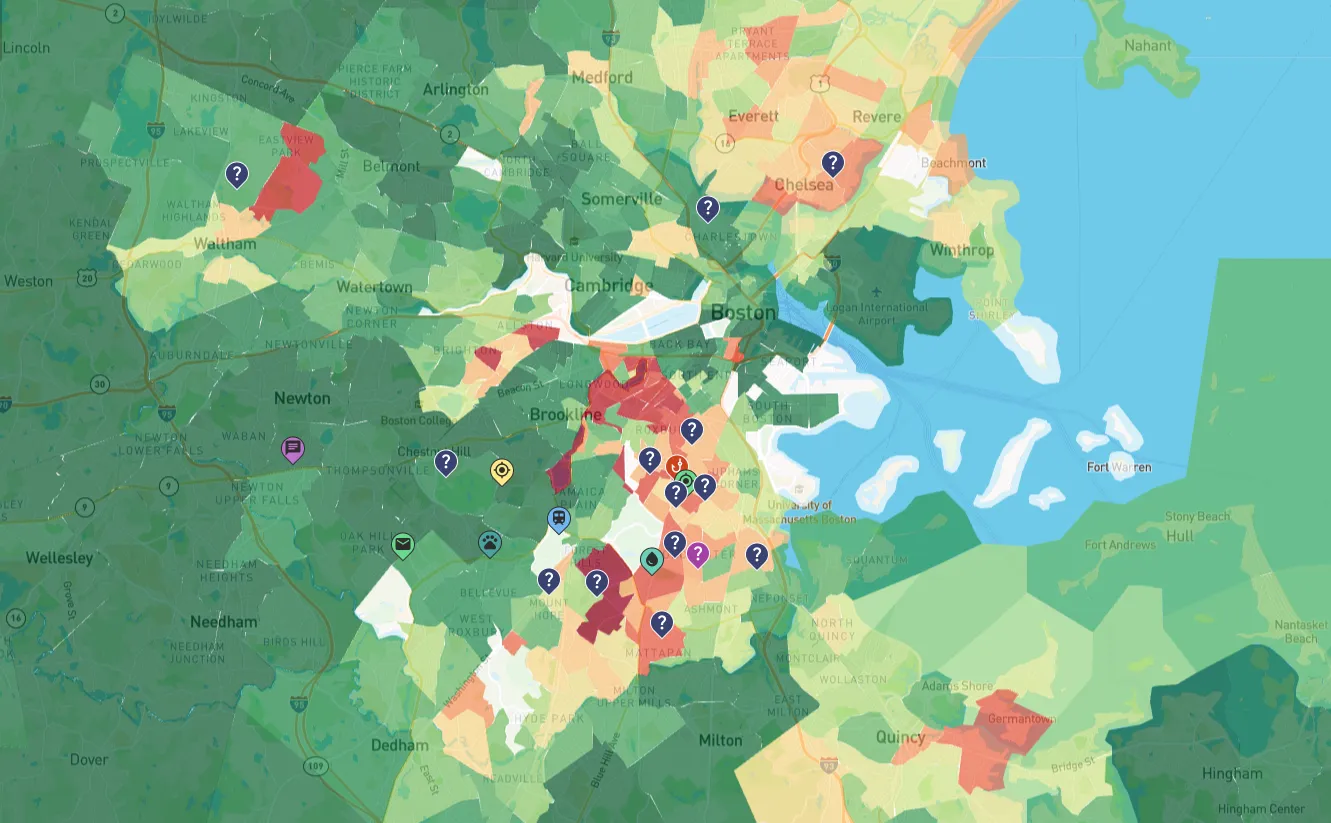

With home prices rising faster than wages, the dream of home ownership is becoming increasingly out of reach for many Americans. The problem is especially acute in coastal cities, where the cost of living is already high. Many cities, including Boston, are forcing developers to build affordable housing. But is it a solution that scales? And is it even a good idea?

With home prices rising faster than wages, the dream of home ownership is becoming increasingly out of reach for many Americans. The problem is especially acute in coastal cities, where the cost of living is already high. Many cities, including Boston, are forcing developers to build affordable housing. But is it a solution that scales? And is it even a good idea?

The idea behind affordable housing is to force developers to sell a fraction of their new construction stock at a steep discount to families below a certain income threshold, a threshold that changes every year. In return, the city allows developers to build more units than the existing zoning code allows, or build units that don't conform to standards (required parking, building dimensions, frontage laws, etc.). Boston prides itself as the city with the largest percentage of affordable housing in the country. with 19% of all housing in the city being affordable. Why is it then that Boston, along with San Francisco and New York, routinely make the top of the list for the most unaffordable homes in the US?

On paper, affordable housing seems like a win-win. Developers get to build more units than they would otherwise be allowed to in a certain region, and some of the residents who would otherwise be priced out of this market are able to purchase a home there. That is, until you realize that the real problem driving the prices up aren't developers, but arbitrary zoning laws placed on land use by the city to begin with. The very politicians claiming to be helping the poor are creating the problem in the first place through artificial land scarcity.

Technology drives prices down, we see this in every single industry except real estate. The biggest factors contributing to the cost of new construction are cost of land and labor. However, if you break "labor" down further, you'll realize that a lot of that cost, like land, is directly tied to governmental bureaucracy rather than actual worker salaries. Cost of land is tied to the building permits attached to it and factors in the time it would take to get a variance (often 2+ years in Boston inner core, based on my own experience).

Labor factors in the cost of a surveyor, architect, engineer, attorney and other professionals, who would often need to go in front of Board of Appeals to advocate for the project. To improve the chance of approval, the developer will need to pay a premium for an architect who has a good relationship with the city and knows how to navigate the bureaucracy. The developer will often be asked to make additional unrelated improvements to the area (rebuilding a local park, for example, or rerunning a new sewer line for the entire street). Most people think cities pay for these improvements, but more often than not, it's local developers who do.

All of this additional cost gets lumped into labor. And while all of these items are nice to have, they make it cost-prohibitive to focus on any type of housing other than luxury. Add holding costs (debt service, insurance) while the paperwork sits on a bureaucrat's desk, and it's not hard to see why luxury housing is the only kind that makes sense to build in expensive cities.

In downtown Boston, new construction projects today are a mix of 80% luxury and 20% affordable (which gets raffled off in a lottery) rather than a project priced in a way the middle class could actually afford without having to fall within arbitrary income limits. If we want housing to actually be more affordable, we need to relax zoning regulations. We have the technology to build more than enough housing units for everyone, as China has already shown us. And while China is not exactly a paragon of quality, economies of scale work just as well in US as other parts of the world. The problem is not lack of housing, but the incentive system we created.

Perverse Incentive System

Artificial scarcity

Zoning and variance regulations make it very hard to increase the density of an area. The recent ADU laws are a good start but they do not solve the existing red tape - variances still cause delays and refusals. The dimensions of old would-be ADU spaces often can't fit the entirety of the footprint that the new regulations require.

Cost of doing business

Construction costs $150-175/sqft in most of the Sun Belt. In Boston, that number is around $300/sqft. Why does it cost 2x as much to build in Boston as in Charlotte? It's not the materials - that cost doesn't vary between states. What does vary is politics, holding costs, labor costs. They propagate in layers, those margins stack. Disposal fees are higher due to policies limiting landfill utilization. Compare $300/ton for landfill use in Massachusetts to $40 in Charlotte. Those costs pass on to the consumer.

Holding costs

These are similar to the cost of doing business, except that these costs are more devious. They sneak up on you. That $8,000/mo interest-only loan really starts to add up when the city takes a year to approve paperwork that would've taken 2 months elsewhere. The system nowadays is mostly electronic, but it's not uncommon to be sent on a wild goose chase that adds delays, or having your file sit unnoticed.

Incentive to build luxury

Luxury housing attracts a premium tenant and covers the overhead premium of doing business in these states. A limited number of affordable housing units are required (17% rounded down), and raffled off via a lottery system to those who fall within income limits. The middle class does not qualify, and gets priced out of the market entirely.

Alternative System

I'm no expert on city policy, but it's clear that all places where affordable housing is a problem share the same factors:

- Limited land due to waterfront

- Artificial scarcity due to policies based on values from over 200 years ago

- Limited incentive to build true affordable housing, affordable for everyone - not just a few lucky lottery winners

- High cost of doing business that needs to be recouped for construction to make sense

- Slow processing times and confusion about the process

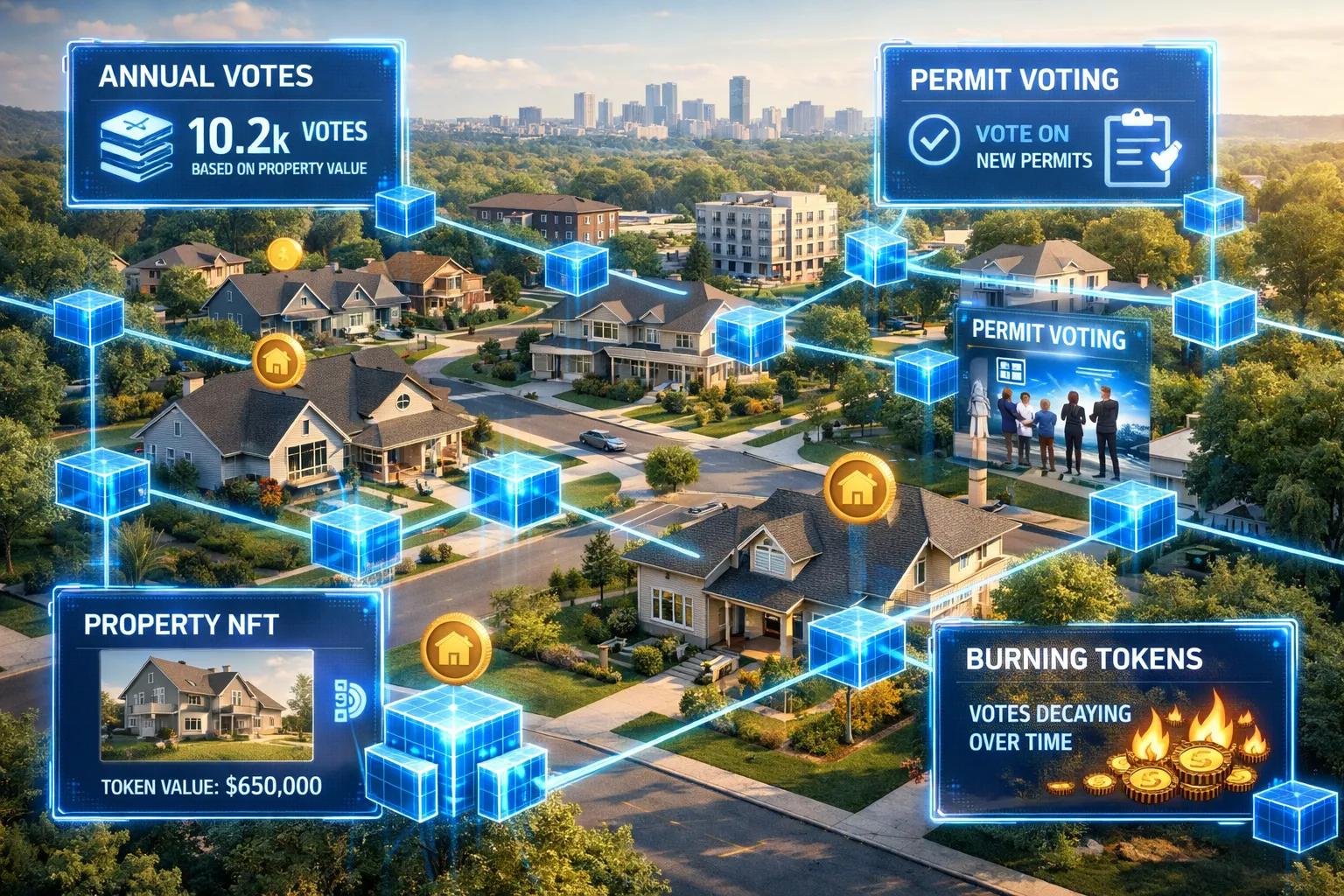

This is a textbook use case for a smart contract. If we were to move the entire permitting process to the blockchain, this is how I imagine it would look like:

- Property owners hold neighborhood tokens, those tokens rebalance every year based on property records (property records would be kept on the blockchain, recorded at the time of quitclaim deed, represented via an NFT token).

- Permit applications would be submitted on the same blockchain by the property owner, ownership is established via an NFT linked to the property address.

- Permits would be auto-approved if they satisfy all the requirements, requirements are published on the blockchain (self-documenting code).

- Requirements would be set by governance vote, proportionally with respect to neighborhood token holders, the longer you stay in the ecosystem (through property ownership), the more voting power you accumulate (great for NIMBYs). But there is a catch...

- Using voting power consumes your tokens, ensuring that you only vote on the issues that truly matter to you.

- To prevent gerontocracy (disproportionate influence of the elderly), we could destroy a fraction of everyone's token holdings every year, making it impractical to store more than 5-6 years worth of tokens using the same mechanism as the current financial system uses to make it impractical to keep cash reserves.

- The same community could then vote to reject a permit while it's moving through the stages. The developer could in theory buy up the tokens to influence the vote, but doing so would effectively compensate the community.

This system could further be integrated with city taxes, the taxes paid to the city would convert to token holdings. Admittedly, this system excludes renters, but should the renters, whose presence is transient, have an influence on neighborhood's future development? One doesn't need to hold the neighborhood token to take advantage of city services, only to vote on the neighborhood direction. Voters decide whether to reject an individual permit, voters decide how to rezone the neighborhood, and which policies to pass - not politicians whose goal is to win populist votes rather than to make the best use of collected taxes.