Gentrification

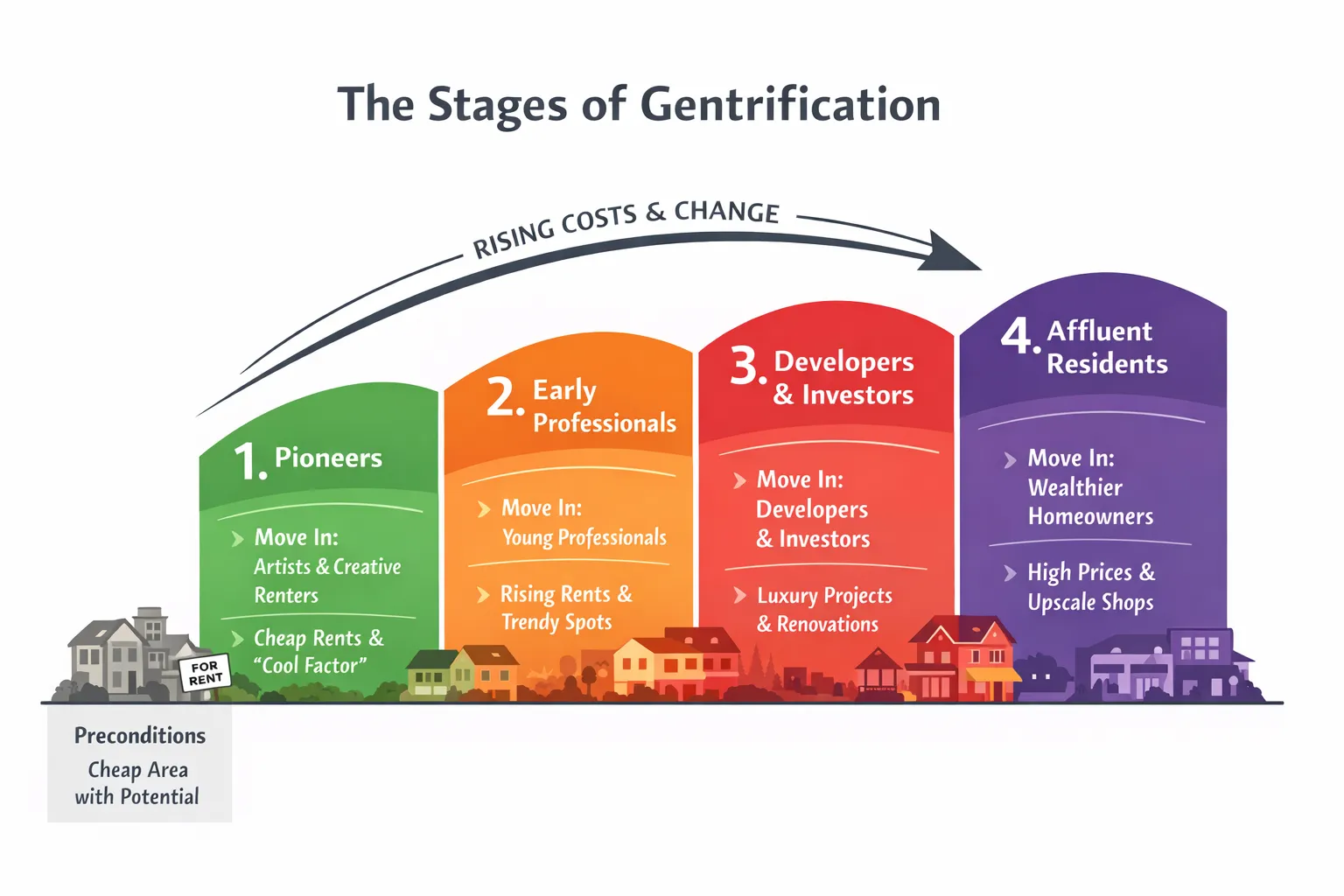

Gentrification was first coined in 1964 by Ruth Glass - a British sociologist. It's the process of a neighborhood’s transformation as higher-income newcomers move in. It has been described as a natural cycle:

Gentrification was first coined in 1964 by Ruth Glass - a British sociologist. It's the process of a neighborhood’s transformation as higher-income newcomers move in. It has been described as a natural cycle:

- The well-to-do prefer to live in the newest housing stock. Each decade of a city's growth, a new ring of housing is built.

- When the housing at the center has reached the end of its useful life and becomes cheap, the well-to-do gentrify the neighborhood.

- The push outward from the city center continues as the housing in each ring reaches the end of its economic life.

In reality the cycle is a lot more complex. The fact that housing stock is at the end of life doesn't necessarily make the area attractive for developers. There are a number of other factors, including access to transportation and local politics. The process also happens in stages, with different participants at each stage, a developer can't simply build a gated community in the middle of a war zone.

Controversy

Gentrification often gets painted as a problem by cities wanting to avoid displacement of existing residents. In reality, however, just like smaller forest fires, it's a necessary part of a healthy city ecology. Neighborhoods age and they need to provide an opportunity for newer generations to move in. A dynamic city can't stay anchored in the past. These market cycles are waves, they expand and contract.

Those who complain about gentrification don't seem to understand the opportunity it affords them to improve their quality of life, to purchase prime rental real estate. Moreover, those same individuals never seem to appreciate the fact they they too were outsiders to this neighborhood once, who took the place of another group that was there before them. Gentrification is not good or evil, it's a force - a wave that investors must learn to detect. You don't need to be early, real estate doesn't move as fast as stocks, but it does move. And failing latch on to it is a sure way to wealth erosion.

What Drives Gentrification? The Mechanism and Market Cycle

Gentrification is fundamentally driven by demand. As cities grow and prosper, more people want to live in convenient, amenity-rich neighborhoods. When the cost of living soars in a city’s most desirable areas, residents and newcomers naturally look to adjacent, previously lower-cost neighborhoods for housing. In other words, gentrification occurs when affluent or middle-class households “filter” into historically working-class or low-income areas, increasing competition for housing there. Economist Jacob Vigdor famously defined gentrification as "an increase in demand to live in a formerly high-poverty neighborhood." (Vigdor, 2023) It’s a market signal that a location - due to proximity, character, or amenities - has been “rediscovered” as valuable.

Urban crime trends have played a big role in this cycle. In the 1970s and 1980s, rising crime and urban decay drove many families to the suburbs. Inner-city neighborhoods suffered disinvestment and decline during this period of “urban flight.” But by the 1990s and 2000s, crime rates plummeted nationwide, making city living more attractive again. As streets became safer and cities invested in transit, parks, and public services, formerly avoided districts began to draw interest from buyers and investors. This reversal of the urban cycle (from decline to revival) set the stage for gentrification in many American cities.

Gentrification Stages

Gentrification can be thought of as a series of demand waves that spread from high-income areas to nearby suburbs with the right conditions. These waves can spread in multiple directions and end mid-cycle if there isn't enough demand.

Stage 0: Preconditions

A neighborhood becomes “available” when there’s a big rent gap: the land is worth more in theory than the buildings earn in practice. This could be for a number of reasons: spillover demand from nearby areas, improvements to transportation bringing new opportunities, or different ways of "repackaging" real estate that weren't available before (e.g. midterm rentals that saw no demand before). As investors, we can't usually force gentrification, but we can buy in an area that's well-positioned to gentrify by studying surrounding suburbs and access to opportunity. You want to buy in the path of progress.

Typical ingredients:

- Close-ish to job centers or transit

- Old housing stock with “good bones” (rowhouses, Victorians, lofty industrial buildings)

- Depressed prices due to disinvestment, crime perception, school quality, or stigma

- Favorable politics - city wants the area to improve rather than exhibiting NIMBYism

Signs to look for:

- Old/cheap housing stock - are homes significantly older than those in other parts of the city? Are they selling for less than those of the surrounding suburbs? Is the discount enough to justify the cost of new construction?

- Proximity to more expensive/desirable suburbs - is this area sandwiched between two expensive regions? Before getting excited, make sure the area has easy access to those other nearby suburbs - if there is a highway separating the two with no convenient access, the effect of gentrification is unlikely to spill over.

- Access to transportation - is this area attractively positioned to jobs and entertainment?

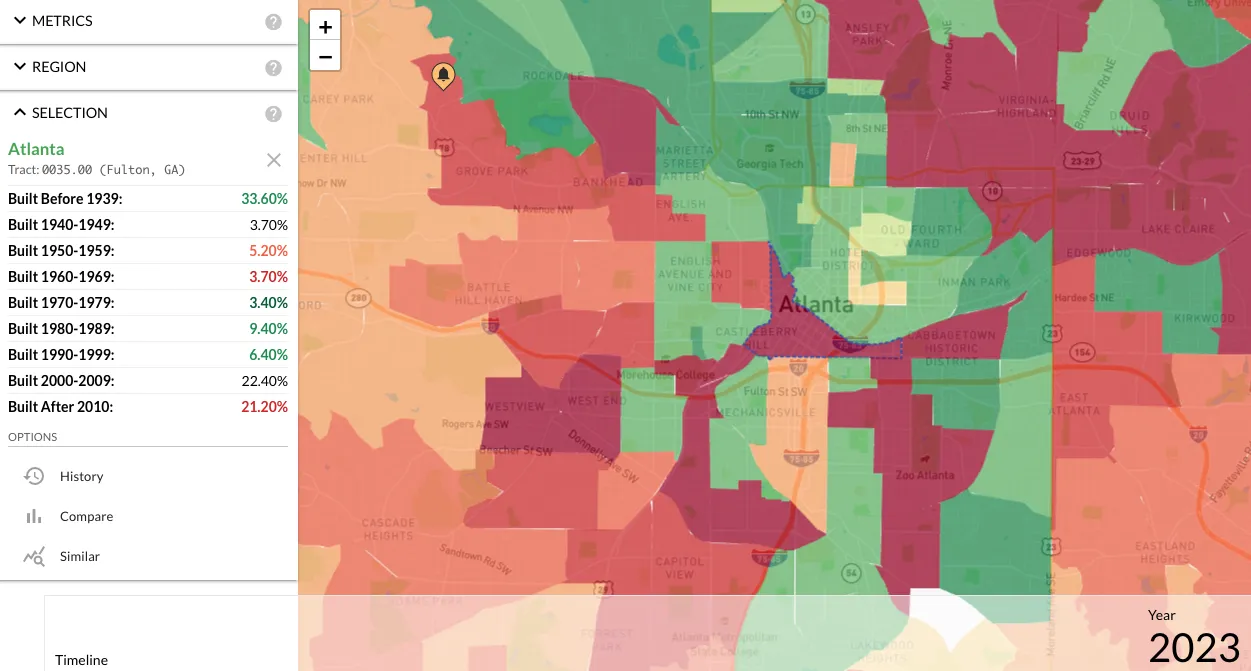

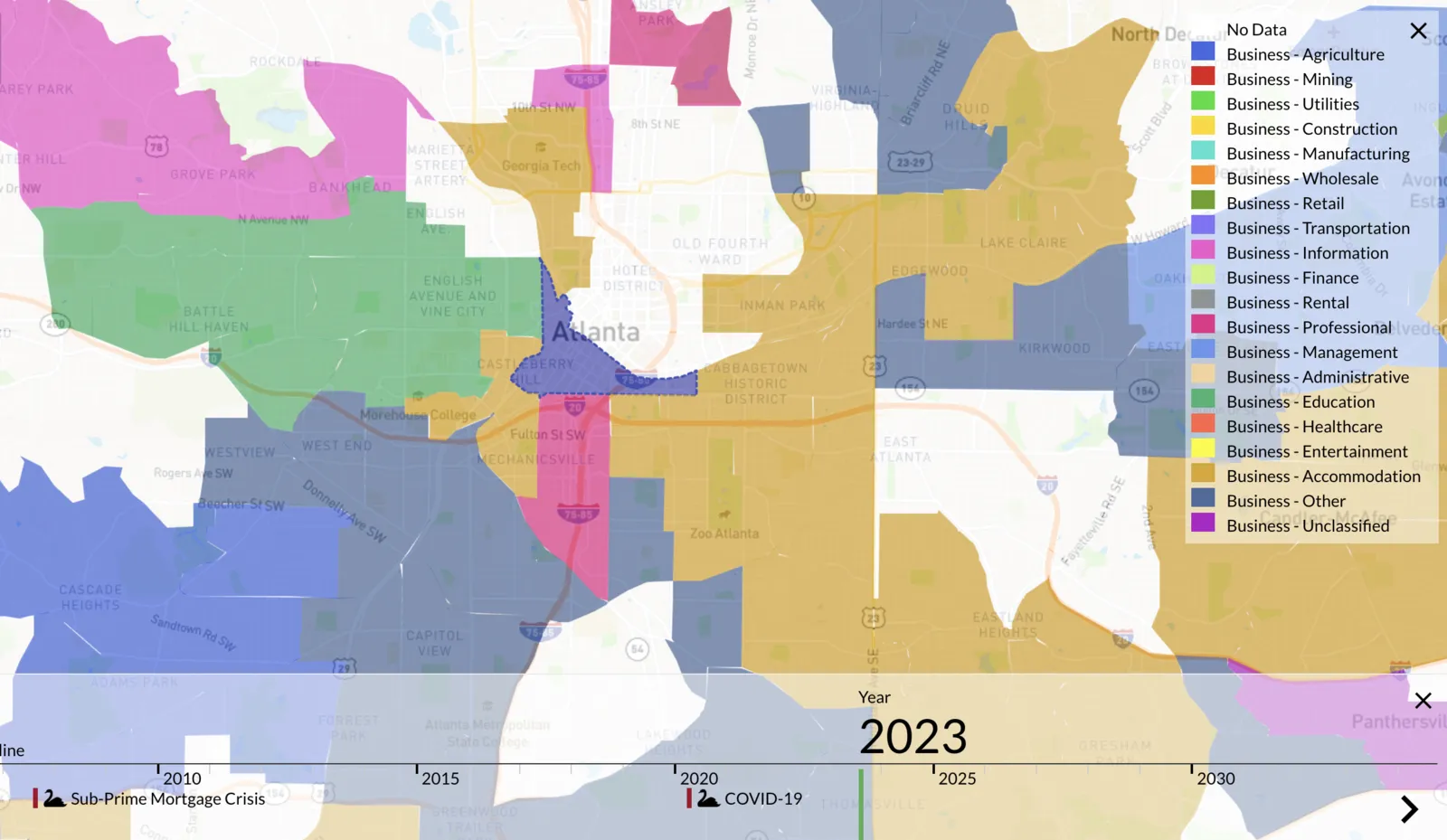

2023 Housing stock distribution by Census tract in downtown Atlanta, source: Investomation

2023 Housing stock distribution by Census tract in downtown Atlanta, source: Investomation

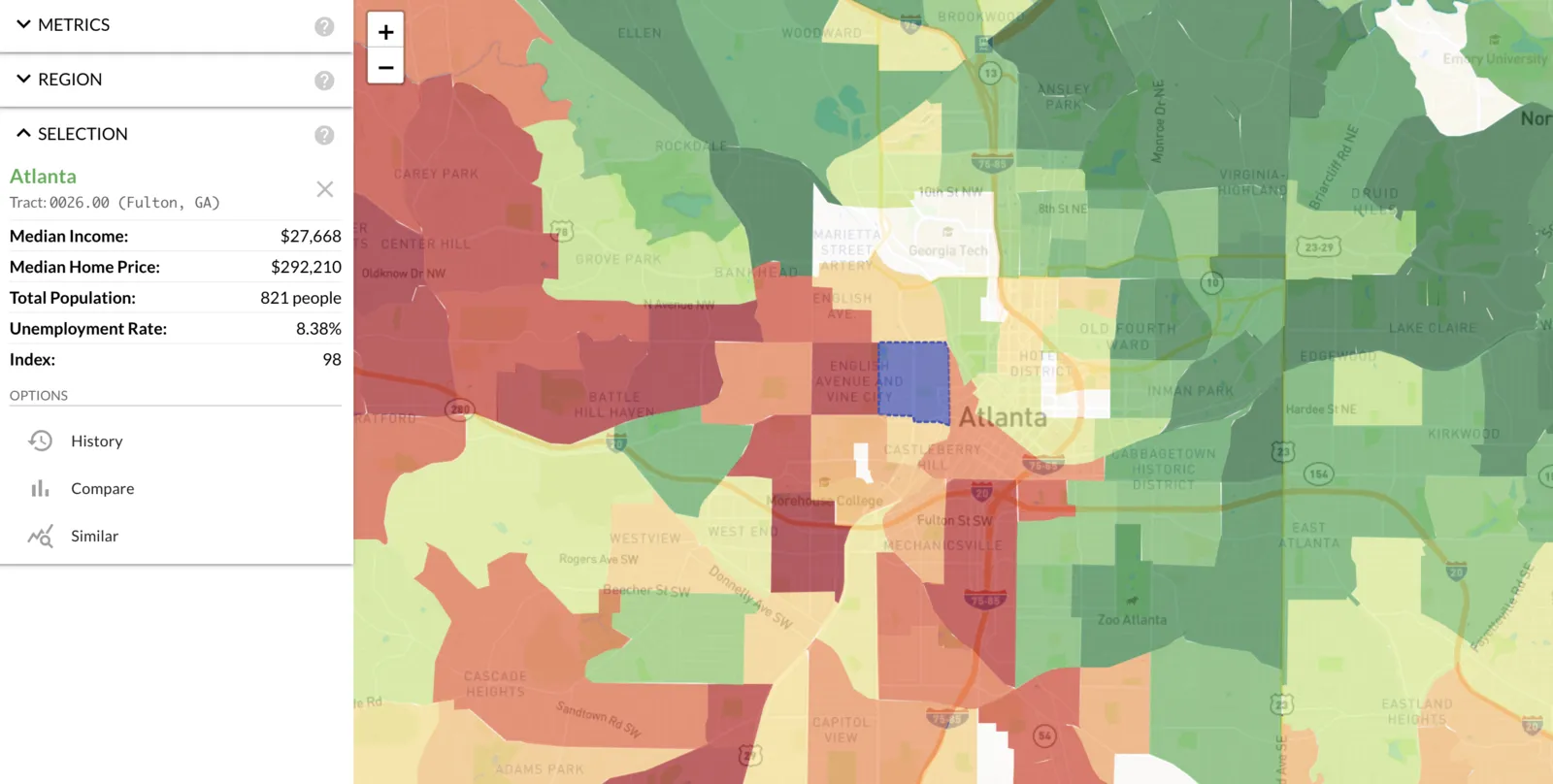

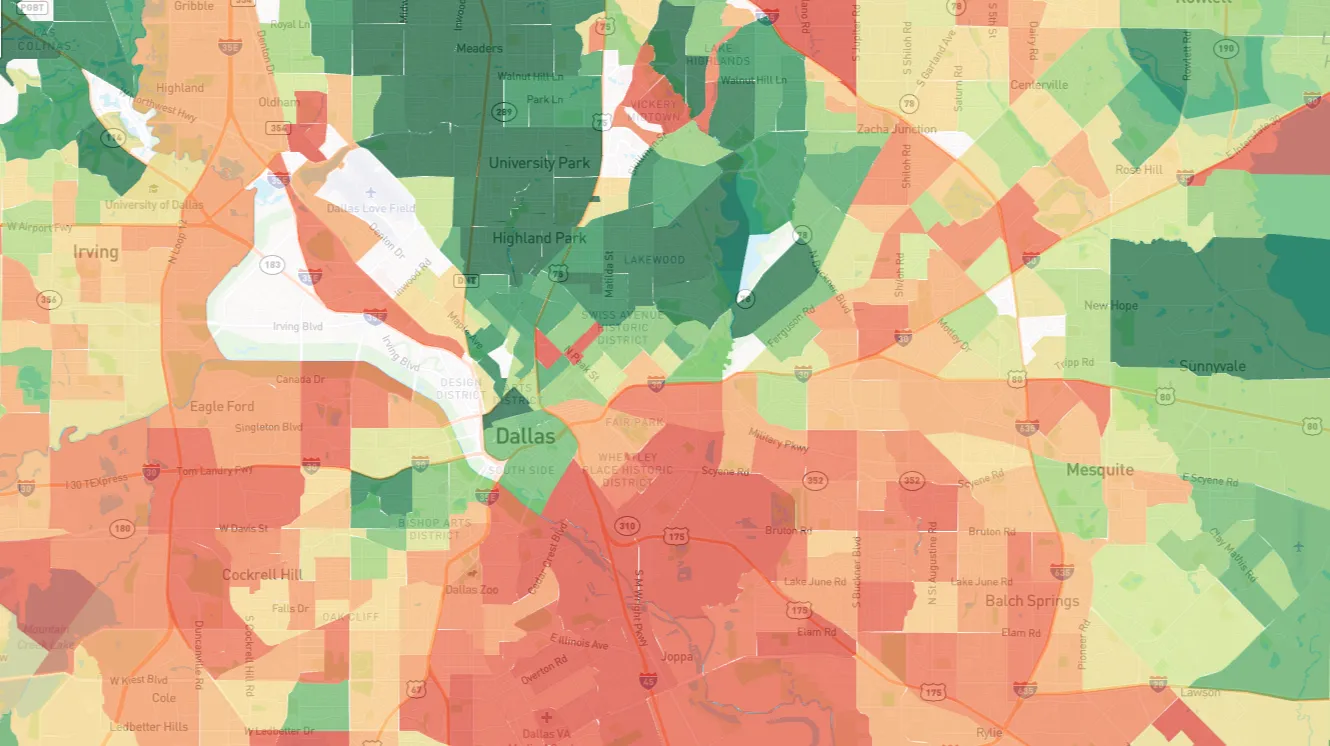

2023 Income, home prices, unemployment, and population by Census tract in downtown Atlanta, source: Investomation

2023 Income, home prices, unemployment, and population by Census tract in downtown Atlanta, source: Investomation

Wave 1: The Pioneers (risk-tolerant renters)

Who moves in first:

- Artists, musicians, designers, grad students

- LGBTQ communities historically (especially when other areas were hostile)

- Young people with low cash but high tolerance for uncertainty

- Sometimes immigrants who find cheap rents and start small businesses

Why they move in:

- They want location and space more than safety or schools.

- They can accept “sketchy” if rent is low and commute is short.

- They’re early adopters of “vibes” and identity. They’ll tolerate rough edges because they value authenticity and community.

What they change:

- They make the area culturally legible: galleries, cafes, DIY venues, street life

- They create the first positive narrative: “this place is up-and-coming”

- They don’t have much money, but they change perception, and perception is the first domino.

Signs to look for:

- Diverging demographics - is the renter base changing? Is it getting younger?

- Diverse racial makeup. While focusing on individual race distribution is not always useful, seeing the racial makeup of the region change is another sign that new tenants are moving in. A healthy market has 2-3 racially diverse tenant groups to choose from.

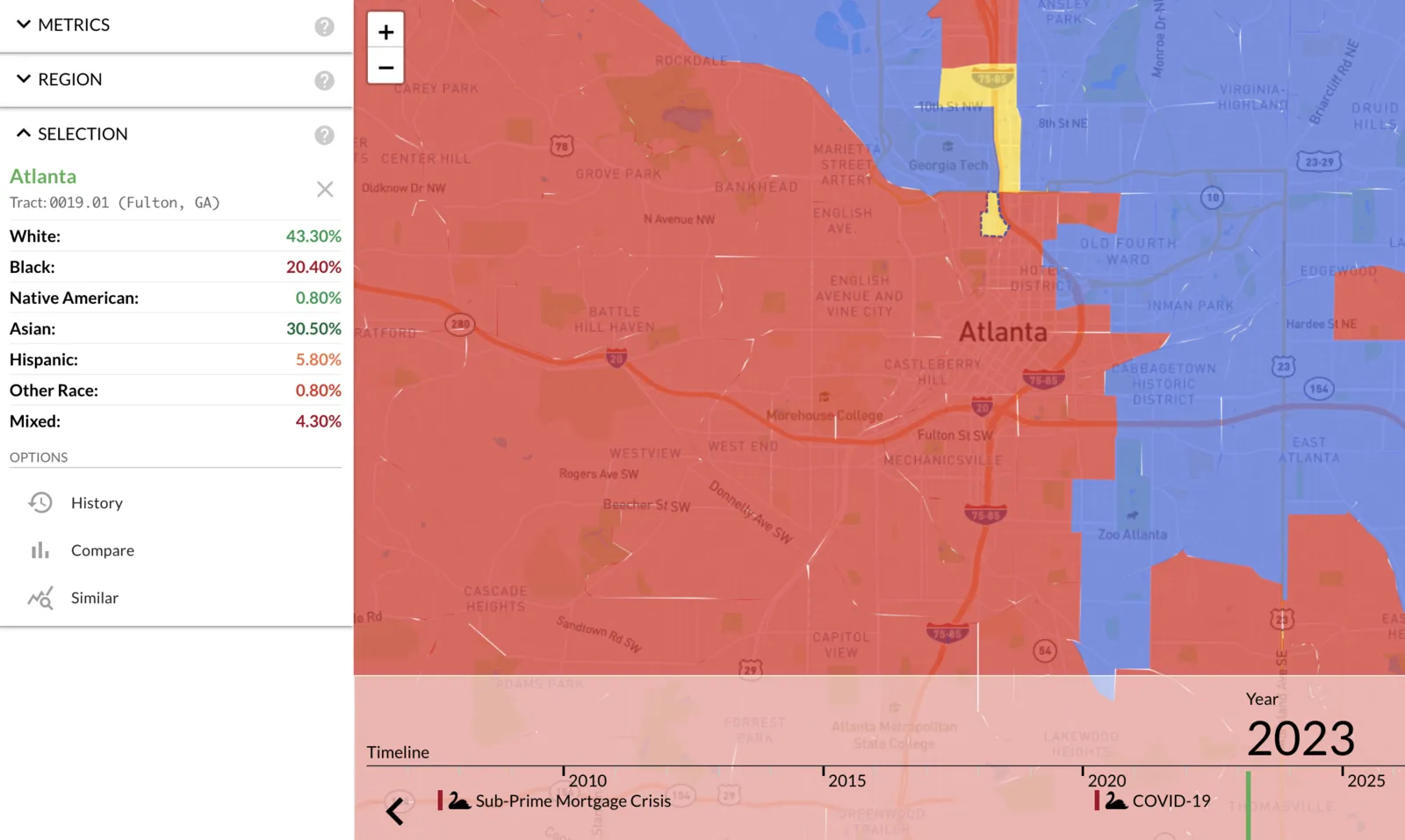

2023 Racial distribution by Census tract in downtown Atlanta, source: Investomation

2023 Racial distribution by Census tract in downtown Atlanta, source: Investomation

Wave 2: The Early Professionals (the first real demand shock)

Who moves in second:

- Young professionals (tech, finance, law, consulting, healthcare)

- Dual-income couples, often renters first

- People who want a “city life” but also want some safety and amenities

Why they move in:

- They’re priced out of the already-nice neighborhoods.

- They’ll pay a premium for “near downtown + cool factor.”

- They have enough income to bid up rents and start setting new comps.

What they change:

- Rents jump faster, because this group can pay more immediately.

- Landlords start upgrading units; “renovated” becomes the new baseline.

- New retail appears that matches their spending: boutique fitness, specialty coffee, nicer bars, higher-priced restaurants.

- This is when displacement pressure becomes real, because the neighborhood starts clearing at prices existing residents can’t match.

Signs to look for:

- Diverging income peaks/distributions, which signify a shift in renter base. Note that simple presence of such divergence in itself is not a sign of gentrification - the trend could be going in reverse instead, with people losing jobs.

- Shift in area's job sectors and employment opportunities.

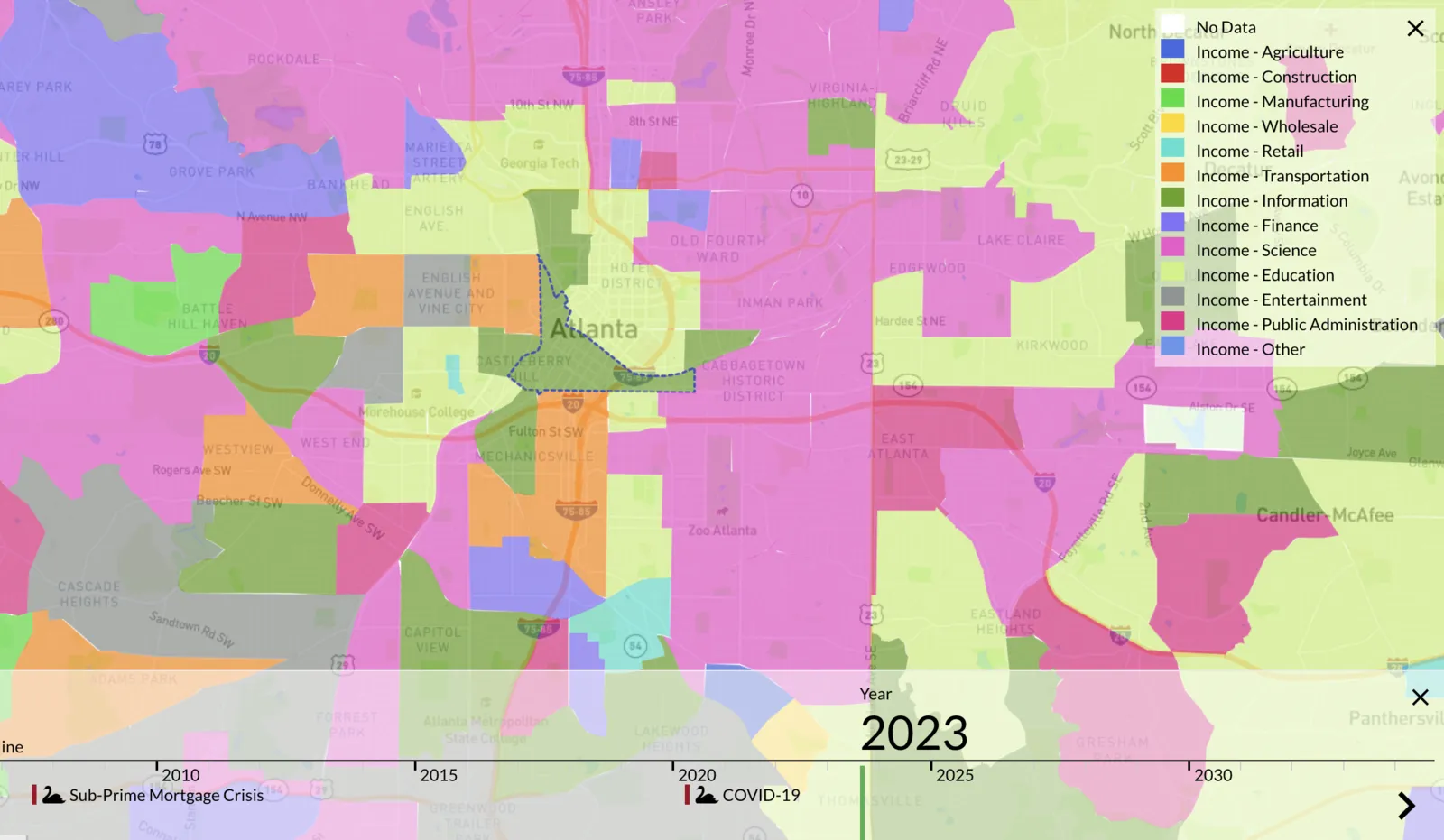

2023 Income source and business distribution by Census tract in downtown Atlanta, source: Investomation

2023 Income source and business distribution by Census tract in downtown Atlanta, source: Investomation

Wave 3: The Capital Wave (developers + institutional money)

Who moves in / arrives third:

- Developers, larger landlords, investment funds

- Higher-income homeowners and families (once schools/safety narrative improves)

- People who wouldn’t have touched the area two years earlier

Why they move in:

- Now the story is proven. Banks lend. Appraisals support deals.

- The “rent gap” can be captured at scale via rehab, upzoning, luxury units, condo conversions.

- The risk premium drops, so big money can underwrite it.

What they change:

- Visible transformation: cranes, large projects, chain stores, polished streetscapes

- Property taxes rise (sometimes sharply), creating a new displacement channel for homeowners

- The cultural identity shifts from local to commercial

- This is where exclusionary displacement kicks in: even if nobody gets evicted, new entrants simply can’t afford to move in anymore unless they’re higher-income.

Signs to look for:

- Increasing number of permit applications and housing starts

- City website actively talking about new development

- Active new development in the community

Wave 4: The “Mature / Luxury” Neighborhood (price ceiling reset)

Who’s left / who arrives:

- Higher-income households, often homeowners

- Executives, families, and sometimes global buyers

- Neighborhood becomes a “safe bet” asset class

Why it happens:

- Scarcity + status. The neighborhood becomes a brand.

- It’s no longer “up and coming.” It’s “established.”

What it looks like:

- Rents and sale prices decouple from local incomes

- Small legacy businesses disappear unless subsidized by loyalty or ownership

- The original “pioneer” class gets priced out too (unless they bought early)

Signs to look for:

- Luxury homes, high incomes and high prices.

- People comparing other areas against the current one in conversations, using it as a measuring stick for neighborhood's status.

Each stage favors a different kind of investor, the investor who finds opportunity early can ride the gentrification wave to the top, provided they can afford the upkeep (rising taxes, utilities, insurance). Rentals help offset the cost of upkeep while the property appreciates. You can then cash-out refinance into another region BRRR-style.

Symptom of Rising Demand

Because gentrification is demand-driven, it’s best understood as a symptom of a city’s success rather than the root cause of housing woes. Trying to “fight gentrification” by freezing a neighborhood in time often backfires. When policymakers artificially restrict development or keep prices below market (for instance, through strict zoning or rent control), they may temporarily shield some incumbent residents - but they inadvertently harm others by squeezing out all new entrants who would gladly pay a premium to live there. In economic terms, whenever you say “yes” to protecting one group from market forces, you are implicitly saying “no” to someone else who values that neighborhood. The uncomfortable reality is that demand will go somewhere - if not accommodated, it can lead to worse outcomes like housing shortages or sprawl.

Consider a real example: Nashville’s historically Black Edgehill neighborhood attempted to ward off gentrification by down-zoning to strictly low-density housing in the 1970s and declaring the area a historic conservation district. The intent was to preserve the neighborhood’s character and keep out luxury development. The result, however, was the opposite. With Nashville’s economy booming, demand for Edgehill still rose - but because new apartments were banned, home prices soared and larger single-family homes replaced the old ones. Over 20 years, Edgehill’s Black population fell by 80% as residents were gradually priced out. Limiting housing supply didn’t stop gentrification, it just made the squeeze on residents more acute by preventing new housing that could absorb the influx of people.

San Francisco’s famous Haight-Ashbury district offers a similar lesson. In the 1970s the Haight - then a diverse, 40% Black neighborhood - was down-zoned to block new development. But tech-driven demand for city living in the Bay Area skyrocketed. With little new housing built, prices in the Haight soared and wealthier buyers moved into the limited stock of Victorian homes. Today, Haight-Ashbury is only around 5% Black, as many lower-income families left in search of affordable options. Rising demand was the real driver - and stifling supply only channeled that demand into displacing the existing community, rather than accommodating both longtime residents and newcomers.

The Economic Benefits of Gentrification

The data shows that gentrification often brings significant benefits - not only for newcomers, but for cities and many long-time residents too. Here’s a structured breakdown of positive impacts:

The data shows that gentrification often brings significant benefits - not only for newcomers, but for cities and many long-time residents too. Here’s a structured breakdown of positive impacts:

Neighborhood Revitalization and New Amenities

Gentrification typically injects new investment into neglected areas, leading to renovated buildings, cleaner streets, and new businesses opening up. Empty storefronts get filled with cafés, grocery stores, boutiques, and other useful services. This infusion of life improves residents’ quality of life by providing goods, services, and entertainment options that previously may have been scarce. It’s common to see formerly blighted blocks come alive with activity as entrepreneurs perceive opportunity. For example, when a neighborhood starts drawing higher-income residents, retail follows – one study found that gentrifying areas see faster growth in the number of retail businesses (Vigdor, 2023) than non-gentrifying areas. In short, revitalization breathes new economic energy into a community. As one overview put it, gentrification can attract new businesses and employment opportunities, bringing much-needed goods, services, and jobs to a low-income area.

Reduced Crime and Improved Safety

A striking positive outcome of many gentrification case studies is lower crime rates. As higher-income residents move in and properties are upgraded, neighborhoods often become safer. There are multiple reasons: a larger tax base can fund better policing; “eyes on the street” increase; private investment in security rises; and a “broken windows” effect (fixing up physical disorder) deters casual crime. A compelling example comes from Cambridge, Massachusetts. In the mid-1990s, Cambridge ended a decades-long rent control policy, which led to rapid gentrification in previously controlled areas. MIT researchers studied this natural experiment and found that crime dropped by roughly 16% in the neighborhoods that gentrified, relative to those that didn’t. This was about 1,200 fewer crimes per year, a substantial public safety gain. Not only did property crimes fall, but even violent crimes decreased as these areas stabilized. The researchers estimated this crime reduction was worth $10–15 million per year in social benefits to Cambridge residents, and that safer streets directly contributed about 10–15% of the property value increase seen post-gentrification. In other words, gentrification made the community safer and more prosperous - a win-win outcome. While every neighborhood is different, many cities (from New York to Washington, D.C.) have seen formerly high-crime districts transformed into considerably safer areas as they gentrified.

Higher Property Values and Wealth Building

By definition, gentrification raises property values in a neighborhood - which is beneficial for homeowners and the local tax base. Owners of homes or buildings often see their equity multiply, creating opportunities to sell at a profit or borrow against increased value to invest further. For long-time homeowners, this can be a windfall: they can cash out on a home that was once of low value and reap significant gains, or simply enjoy increased net worth. Even renters can indirectly benefit if they eventually buy elsewhere using savings or if new development increases housing supply citywide. At a city level, rising property values translate into higher property tax revenues, allowing municipalities to reinvest in public services, schools, and infrastructure. An analysis by the National Civic League notes that gentrification brings “a higher tax base, revitalizes previously derelict neighborhoods, improves public safety, and attracts newcomers to boost the economy.” All these forces can create a virtuous cycle of further improvement.

Economic Growth and Job Opportunities

Gentrifying neighborhoods typically see an uptick in construction and service jobs. Renovation of housing, new construction projects, and opening of businesses all create employment. From construction crews to baristas, these developments employ people (often including existing community members) and stimulate the local economy. One study highlighted that residential redevelopment spurs job growth - e.g. building or refurbishing homes employs construction workers, and new stores hire staff. Moreover, as a neighborhood’s population and income grow, local consumer spending increases, further boosting business revenues and job creation. In the long run, successful revitalization can attract offices or startups, bringing even more diverse employment to the area. A formerly marginalized district can turn into a new economic hub of the city. For instance, Pittsburgh’s downtown Cultural District, launched in the 1980s to revive a dilapidated area, drew theaters, restaurants, and galleries that not only created jobs but also made the city a more attractive destination for talent. New investment can truly “lift all boats” in the neighborhood - entrepreneurs, workers, and the city treasury all stand to gain.

Better Infrastructure and Services

Along with private investment, gentrification often comes with public investment in infrastructure. City officials are more likely to upgrade roads, transit, parks, and utilities in a neighborhood on the upswing. Think of streetlights being fixed, new bike lanes, cleaner parks, and expanded public transit routes. These improvements benefit all residents – new and old. For example, when a district gains political and economic clout, things like sewer upgrades or new schools that were long neglected may finally get funded. Gentrification also correlates with improved city services like sanitation and policing as municipal resources flow to the rejuvenated area. The neighborhood becomes not only more aesthetically pleasing but functionally better - with potholes fixed, transit more reliable, and new community facilities (libraries, recreation centers, etc.) opening up. All residents enjoy a higher quality of life due to these upgrades.

Lower Concentrated Poverty and More Socioeconomic Mixing

One underappreciated benefit is that gentrification can break up concentrations of intergenerational poverty, which are known to harm life outcomes. As middle-class families move into a poor neighborhood, the area often becomes more mixed-income over time. This can bring new social networks, better resourced schools (due to active PTA members or alumni), and a reduction in the social problems associated with segregated poverty (crime, poor health outcomes, etc.). A comprehensive study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia (covering 100 metro areas) found that when low-income neighborhoods gentrify, the poverty rate in the neighborhood tends to drop significantly (by about 3 percentage points on average). Crucially, many original residents remain to enjoy this improved environment. Brummet and Reed, the study’s authors, linked individual census records over a decade and discovered that even in rapidly changing areas, roughly 70% of the original residents were still there after 10 years. They conclude that “gentrification creates substantial benefits for long-time residents of low-income neighborhoods, and causes little displacement.”. Those who stay experience lower exposure to poverty and crime, better amenities, and often better opportunities for their children (e.g. through improved local schools or simply growing up in a less disadvantaged area). Even those who do move out aren’t necessarily worse off - the study found no evidence that movers from gentrifying areas end up in poorer neighborhoods than movers from non-gentrifying areas. In essence, many low-income families either stay and benefit from neighborhood uplift or move on by choice (often using increased home equity or taking advantage of new opportunities) rather than being forcibly “expelled” to markedly worse conditions.

Citywide and Regional Gains

Gentrification’s benefits radiate beyond the neighborhood itself. A city is an interdependent economic ecosystem. Revitalizing one district can reduce burdens on others, for example, fewer high-crime “no-go” zones means less strain on police and emergency services citywide. A larger urban tax base can support services in all neighborhoods. And when a city retains and attracts middle-class residents instead of losing them to suburbs, it curbs sprawl and long commutes, which has environmental and infrastructure benefits regionally. Gentrification can thus be seen as part of a healthier urban growth pattern: better utilization of existing city land and resources. Rather than building new subdivisions in far-flung suburbs, society is investing in renewing central neighborhoods, which is more sustainable. Overall, economists often argue that the net effect of gentrification on urban welfare is positive – it’s essentially a reallocation of people to places where they derive higher satisfaction, combined with capital investment that raises the productivity and livability of that area. There are, of course, individual winners and losers, which we’ll address next. But from a “city as a whole” perspective, gentrification tends to boost aggregate quality of life and economic output, which is why cities that never gentrify (remaining in a cycle of decline) often struggle far more with poverty and job loss.